| Ročník: 2023 | Volume: 2023 |

| Číslo: 1-2 | Issue: 1-2 |

| Vyšlo: 31. ledna 2024 | Published: Jan 31st, 2024 |

| Iľko, Ivan - Peterková, Viera.

The impact of pandemic measures on the behaviour of science students.

Paidagogos, [Actualized |

#7

Zpět na obsah / Back to content

The impact of pandemic measures on the behaviour of science students

Abstract: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the lives and daily routines of people almost everywhere on the planet. Suddenly, working or studying remotely became common for millions of people. In this context, we examine how the daily activities of students in natural science subjects in the field of sports, sleep, work, leisure, eating, and hygiene changed in the context of Slovak Republic. Based on a sample responses collected through an ethogram in April 2021 and subsequently in April 2022, we found through statistical analysis that the behavior of students changed significantly during the pandemic in the area of sleep (p= 0.038). We also found that the behavior of students was not statistically significantly different in the areas of sports, work, leisure, eating, and hygiene. These findings provide a basic characterization of the behavior of students in natural science subjects at a university in Slovak Republic. In the event of another lockdown and deteriorating of epidemiological situation, these findings can provide support to students as well as university educators.

Keywords: Pandemic, COVID-19, behavior, students, social.

1. Introduction

The term pandemic was firstly used in the mid of 17th century to describe continuously spreading disease. These terms do not necessarily describe only infectious diseases but also non-infectious diseases, illnesses commonly known as civilization diseases such as cancer or hypertension. An endemic disease is a disease which occurs in the same area as for example town, country or even continent. An epidemic is a disease which affects large population within the same country or region whereas pandemic is an epidemic that expands to several countries or continents (Sampath et al., 2021). The majority of human infections are caused by cross-species transmission of microorganisms from animals to humans (Stephens et al., 2021). Most animal pathogens are not readily transmitted to humans, and for an animal pathogen to become human pathogen it must evolve into pathogen, which is capable of not only infecting humans, but also maintaining long term human to human transmission. Examples of these pathogens are West Nile virus or Nipah rabies, Ebola or mankeypox viruses (Pike et al., 2010; Wolfe et al., 2007; Ifediora & Aning, 2017). As humans increase the interactions with animals through hunting, butchering, trading of animals and animal products, animal husbandry, and the domestication of animals and exotic pets, the probability of cross-species transmission increases. In the early 20th century, the hunting and butchering of non-human primates led to the introduction of simian immunodeficient virus into the human population, giving rise to current HIV pandemic. In general, hunting and butchering is the gateway for the zoonotic transmission of retroviruses (Pike et al., 2010). Because the number of zoonic outbreaks appears to be increasing, better understanding is crucial for decreasing the risks these pandemic diseases may have on human population. In 1985 was an outbreak of salmonellosis in the United States infecting more than 160 000 people (Forshell & Wierup, 2006). In 1978 there was an outbreak of Oropouche virus in Brazil and the estimated number of infected humans was 227 000 (Pinheiro & Travassos, 1981). The second latest outbreak was H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009-2010 causing 123 000 to 400 000 global deaths. Even the latest Covid-19 pandemic is estimated to have infected 200 million people causing around 4 million deaths (Stephens et al., 2021). Diving deeper into the history, there were few more very significant pandemics (Gross, 2022; Scalera & Mossad, 2009). The Spanish flue pandemic belongs to the group of the most devastating pandemics. Even though it lasted only for about a year, the number of deceased is enormous due to the high morbidity pattern (affected mostly young and healthy person), rapid disease progression and death caused by a multiorgan failure. Although Spanish flue did not originate in Spain there is now a worldwide consensus about the name of this disease (Trilla et al., 2008). Another big pandemic was the pandemic of the black death. It swept across Europe in 14th century during 1347 to 1352 killing almost half of the population in some areas. It is considered to be one of the mankind’s worst pandemics caused by Yersinia pestis. Y. pectis is Gram-negative bacteria which belongs to the enterbacteria family (Raoult et al., 2013). Another illness caused by bacteria Vibrio cholerae is cholera. This bacteria has caused several pandemics since 1817. Cholera is life-threatening, diarrheal disease with high morbidity and mortality. Cholera outbreaks were observed on every continent except Antarctica. The current cholera pandemic started in 1961 in Makassar and continues to be a major health problem with 3 million to 5 million infection cases every year (Hu et al., 2016). In 2018 to 2019 Zimbabwe experienced another outbreak with more than 10,000 suspected cases (Mashe et al., 2020).The last cholera pandemic is still ongoing, started in Indonesia and spread to more continents than the previous six cholera pandemics. It is transmitted by contaminated water and the latest outbreak happened in Somalia in 2021 (Sampath et al., 2021). HIV is human immunodeficiency virus which has caused over 20 million deaths since its first identification and an estimated number of people worldwide currently living with HIV is 36 million. The region most affected by this virus is Sub-Saharan Africa where at the end of 2000 the estimated number of people living with this infection was over 25 million and Sub-Saharan Africa has accounted three quarters of the global death toll (Piot et al., 2001). The burden remains relatively stable, even declined in some countries which is probably the result of increased use of sexual protection or increased use of antiretroviral treatment. HIV virus causes progressive loss of CD4 T lymphocytes, which help with fighting infections by triggering the immune system to destroy foreign pathogens. After several years, serious immunodeficiency emerges and affected individuals suffer infections or other oncological complications. The course of this pandemic has changed due to highly effective antiretroviral therapy which is available for over 2 decades. Suppressing of HIV replication leads to improving of immune functions and reduction of risk of developing AIDS. However, this treatment is not curative and when the administration is stopped, the virus rebounds within weeks (Deeks et al., 2015). The latest pandemic that mankind suffered was the outbreak of pneumonia of unknown origin in December 2019. The outbreak was reported in Wuhan in China, and this was the 7th human coronavirus outbreak. Since then, the virus has spread all over the world and in May 2020 the estimated number of infected was more than 4.8 million people and caused more than 300,000 deaths (Ciotti et al., 2020). Coronaviruses are enveloped viruses with positive single-stranded RNA that infect humans but also animals. The SARS-CoV-2 has apparently been successful in transition from animals to humans probably on a seafood market however potential efforts to identify intermediate hosts have been neglected and the route of transmission is not clarified. Coronaviruses were first detected and identified in 1966 and were cultivated from patients with common cold. Their name comes from Latin (corona – crown) because of their spherical virions with core shell and surface projections resembling solar corona. Coronaviruses are classified into 4 subfamilies alpha-, beta-, gamma-, and delta- from which alpha- and beta-originate from mammals especially bats and gamma- and delta- originate from pigs and birds (Velavan & Meyer, 2020). SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome), SARS-CoV-19 and SARS-CoV together with MERS (Middle east respiratory syndrome) MERRS-CoV cause sever pneumonia, while the other human coronaviruses (OC43, NL63, HKU1, 229E) cause diseases with mild symptoms. Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 infection present mild to severe symptoms with large portion of infected being asymptomatic carriers. The most common reported symptoms are fever, cough, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal symptoms including vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. The transmission of respiratory viruses is through respiratory route in a form of droplet transmission or aerosols. Oral-fecal route may also be another form of transmission since the SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in the stool of patients suffering from COVID-19 pneumonia. SARS-CoV-2 has also been detected in saliva of infected patients and on inanimate surfaces like door handles, cell phones and person which came into contact with contaminated surface may be infected through eyes, mouth or nose. The estimated incubation period was 5.1 days and 97% of infected individuals develop symptoms within 11 days (Ciotti et al., 2020). Through history, epidemics and pandemics have caused huge loss of lives. When pandemic occurs, it causes chaos and distress in human lives, and population is concerned about the spread of disease, together with the ability of governments to deal with situation like this. The main efforts of governments are identifying the source of infection and its spread, management of acute medicinal needs and less attention is paid to mental health of infected or society in general. The common strategies for controlling the extension of disease are quarantine imposed to individuals, parts of community or the whole community, travel restrictions, wearing face protection and social distancing, banning large gatherings, or developing vaccines (Usher et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2019). The strongest and most effective weapon that society has against this virus that is affecting not just health but also economics, politics, and social order, is the prevention of its spread. The main points in preventing the spread in society are hand hygiene, desinfection, social distancing and quarantine (Güner, Hasanoğl & Aktaş, 2020). To disinfect the environment, mainly chemical disinfectants are being used robustly. However, due to panic state, fright, and unawareness, people are using it violently, which can have an adverse effect on human health and environment (Rai, Ashok & Akondi, 2020). Proven effective strategies against SARS-CoV-2 transmission: vaccination, using masks consistently and correctly, maximizing ventilation and filtration of air, staying home when sick, handwashing, and regular cleaning of high-touch surfaces should also be encouraged (Christie et al, 2021). The latest COVID-19 pandemic has significantly influenced life of people all over the world. Terms like “self-isolation” or “social-distancing” became a part of everyday life and with the effort of citizens to get accustomed with this has drastically and suddenly caused many radical changes in peoples’ daily routines and lifestyle in general. Long lasting social isolation can lead to boredom and stress which may in some individuals lead to greater tendency to overeating or developing unhealthy habits. Moreover, prolonged staying at home may induce increase in screen time, whether work related or not, and reduce outdoor activities thus augmenting sedentarism. Apart from all the negative effects social isolation has on individual’s lifestyle like eating or performing sport activities it can also negatively affect the sleep pattern or quality of sleep (Kumari et al., 2020) even the shopping habits. With governments closing schools, restaurants, some shops and public services fear was spread along the whole population dramatically changing everything people were previously used to. With the growing population, people living closer to animals, the transfer of new viruses to human population will occur more frequently. With the COVID-19 pandemic, it is very difficult to estimate the long term effects it had, has and will have on economy, behaviour or society in general probably also because these aspects have not been studied to a great extent in the past. On the other hand, online entertainments, online communication and online shopping are seeing unprecedented growth (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). In this paper, we examine how the daily activities of science students in the areas of sport, sleep, work, leisure, diet and hygiene have changed in the Slovak Republic during the pandemic measures.

Materials and Methods

The pedagogical experiment took place at the Faculty of Education, Trnava University in Trnava, Priemyselná 4, 917 01 Trnava. Before conducting the experiment, we prepared a sample template of an ethogram divided into several main areas (sport, sleep, work, free time, eating, and hygiene) and sub-areas. The ethogram contained 14 items, of which 6 were the main ones. The ethogram method is commonly used in the study of the behavior of people of different ages (Sanchez-Martin et al., 2001; Barbosa, 2016; Weisfeld & Goetz, 2013). The prepared template was distributed among 18 natural science students aged 22 to 24. We chose undergraduate students for the experimental group. The experimental group consisted of 18 students, including 1 boy and 17 girls (Tab. 1). The low number of respondents was due to the complicated situation during the COVID-19 pandemic, while the predominance of girls in the study could be caused by the preference of natural science subjects by the female gender (Wandersee, 1986; Prokop, 2007). Other authors have also used a research sample with a number of approximately 20 respondents (Anderson & Gerbing, 1991; Kielhofner, 1986). The ethogram was distributed during pandemic measures, strict lockdown with a ban on going out, and distance learning (from 12.4. - 18.4.2021). The ethogram was distributed and collected online through Microsoft Excel. There were five lockdowns in Slovakia from 2020 to the end of 2021. Our research was conducted during the third lockdown in Slovakia, thus eliminating the effect of the first lockdown associated with finding a daily routine, etc. The second repetition of the ethogram took place approximately at the same time a year later (from 4.4. – 10.4.2022). The students recorded 10080 minutes, which represents the length of 7 days during pandemic measures and after their cancellation. All involved students participating in the research, and no one was excluded during the research. The students of the experimental group were selected by available sampling. Through the above-described tools of our research, we obtained data that we further subjected to statistical analysis in Statistika 12 and Microsoft Excel Version 16.49/2021 programs. At the beginning, we conducted a normality test (Shapiro-Wilk test), and we found that the sample did not have a normal distribution. We compared the average scores from the obtained responses in individual areas (sport, sleep, work, free time, eating, and hygiene) using the Wilcoxon paired test, which is suitable for non-normal distribution of the studied sample.

Results

We divided the results section into six areas: sports, sleep, work, leisure time, eating, and hygiene. This division corresponds to the areas in the ethogram.

Section of sport

In the mentioned section, we focused on examining the change in the behavior of students in the field of sports during pandemic measures with distance learning compared to the behavior of students during in-person learning, after the end of pandemic measures. We calculated the average time that students spent on sports in both observed conditions. We expressed the calculated average as a percentage. During pandemic measures, students devoted 5.76 % of the total observed time to sports. After the cancellation of pandemic measures, students devoted 5.02 % of the total observed time to sports. We did not observe a statistically significant difference (p = 0.4008) in the time spent on sports during pandemic measures and after their cancellation (Graph 1).

Section of sleep

In the given section, we focused on studying the changes in students' behavior in the area of sleep during pandemic measures with distance learning compared to students' behavior during in-person learning after the pandemic measures ended. We calculated the average time that students spent on sports in both observed conditions. We expressed the calculated average as a percentage. During the pandemic measures, students spent 32.81% of the total observed time on sleep. After the pandemic measures were canceled, students spent 35.03% of the total observed time on sleep. We found a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0381) in the time spent on sleep during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation (Graph 2). Students spent less time on sleep during the lockdown and strict pandemic measures.

Section of work

In the given section, we focused on examining changes in students' behavior in the area of work during pandemic measures with distance learning compared to students' behavior during in-person learning after the pandemic measures ended. We considered preparation for teaching as the area of work. We calculated the average time that students spent on work in both observed conditions. We expressed the calculated average as a percentage. During the pandemic measures, students spent 34.09% of the total observed time on work. After the pandemic measures ended, students spent 34.89% of the total observed time on work. We did not find a statistically significant difference (p = 0.5146) in the time spent on work during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation (Graph 3).

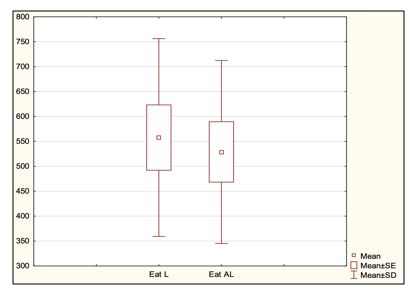

Section of eating

In this section, we examined changes in students' eating behavior during distance education pandemic measures compared to students' eating behavior during face-to-face, post-pandemic measures. We calculated the average time students spent eating in both conditions studied. We expressed the calculated mean as a percentage. During the pandemic measures, students spent 5.90% of the total observed time on eating. After the lifting of the pandemic measures, students devoted 5.23% of the total observed time to eating. We did not observe a statistically significant difference (p = 0.6784) in the time spent eating during the pandemic measures and after the lifting of the pandemic measures (Graph 4).

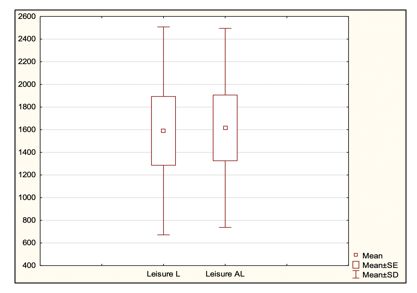

Section of leisure time,

In this section, we investigated the change in students' leisure behaviour during the distance learning with pandemic measures compared to students' behaviour during the face-to-face, post-pandemic pandemic measures. We calculated the average amount of time that students spent on leisure in these two conditions studied. We expressed the calculated average as a percentage. During the pandemic measures, students spent 16.84% of the total observed time on leisure. After the lifting of the pandemic measures, students devoted 5.23% of the total observed time to leisure. There was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.5939) in time spent on leisure during and after the pandemic measures were lifted (Graph 5).

Section of hygiene

In that section, we examined the change in students' hygiene behaviour during the distance learning pandemic measures compared to the behaviour of students during the face-to-face, post-pandemic pandemic measures. We calculated the average time students spent on hygiene in both conditions studied. We expressed the calculated mean as a percentage. During the pandemic measures, students spent 4.60% of the total observed time on hygiene. After the lifting of the pandemic measures, students spent 3.70% of the total observed time on hygiene. We did not observe a statistically significant difference (p = 0.6744) in the time spent on hygiene during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation (Graph 6).

Discusion

In a similar way to how we divided the results section, we also processed the discussion section, dividing it into six areas: sports, sleep, work, leisure, eating, and hygiene. This division corresponds to the areas of the ethogram.

Section of sport

We did not observe a statistically significant difference (p = 0.4008) in the time spent on sports during pandemic measures and after their cancellation. Di Renzo et al., 2020 performed a study about the changes in lifestyle of total 4500 Italian participants who answered a questionnaire, and after validation, 3533 respondents have been included in the study of wide range from 12-86 years Regarding the overall change in lifestyle 46.1 % of participants declare there was no change in their habits while 16.7 % have declared their lifestyle improved, and 37.2 % state their lifestyle has been worse. According to the results presented by this study, smoking habits of participants have been reduced. Concerning physical exercise, no significant difference has been observed comparing the percentage of people that did not train before, nor during pandemic. Comparing people who did exercise 1-2- times a week there has been a slight decrease, 6.9 % regarding doing exercises before pandemic and during. On the contrary, participants who stated performing exercise more than 5 times a week observed a higher increase in the frequency of exercise during pandemic than before pandemic (Di Renzo et al., 2020). Similar results have been reached by Mutz et al., 2020 which state that overall, German population has reduced their level of exercise during pandemics (Mutz &Gerke, 2020). Results of Mutz et al., 2021, Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020, and Mascherini et al., 2021 also states that the participants experienced decreased level of leisure time sport activities compared to pre-pandemic period (Mutz & Reimers, 2021), (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020), (Mascherini et al., 2021). The respondents in research of Grant et al., 2021 also stated that the sedentary lifestyle had severe impact on their exercise level and 64.5 % of respondents did not perform exercise as recommended (Grant et al., 2021). Raiola & Di Domenico, 2021 conducted similar study and according to his results most of the participants continued their exercise but only one third continued their outdoor training and the rest preferred indoor training through online platforms (Raiola & Di Domenico, 2021). Kaur et al., 2020 support findings of Gaetano et al., 2021 saying that most of the people performing leisure sport activities stopped during pandemic waiting for things to get back to normal, but after they accepted the reality they preferred using alternative online platforms for performing exercise at home (Kaur et al., 2020). According to Keshkar et al., 2021 and Timpka, 2020 the effects of pandemic on sport industry have been so severe and deep that they will remain in some ways also in the post-pandemic period even though the consequences are hard to predict (Keshkar et al., 2021; Timpka, 2020). The cited studies confirm our findings, as we did not observe a change in behavior in the area of sports during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation.

Section of eating

We did not observe a statistically significant difference (p = 0.6784) in the time spent eating during the pandemic measures and after the lifting of the pandemic measures. Regarding eating habits Di Renzo et al., 2020, from the total participants of research more than half of them has felt a change, 17.7 % had less appetite and 34.4 % had more appetite. The data also showed that during the pandemic emergency there was an increase in homemade recipes, cereals, legumes, white meat and hot beverages intake while the consumption of fresh fish, baked products, delivery food and alcohol intake was decreased (Di Renzo et al., 2020). Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020 also mentioned that the 49.4 % of respondents preferred home-cooked meals (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020). Research of Sgroi et al., 2022, Alhusseini et al., 2020, and Mascherini et al., 2021 also states that families recorded increase in home-cooked meals which has positively affected their diet qualities compared to take-away food rich in saturated fats and refined sugars, and low in dietary fibers and micronutrients. The main reason was greater availability of time which has been a barrier in the preparation of home-cooked meals before pandemic (Sgroi & Modica, 2022; Alhusseini & Alqahtani, 2020; Mascherini et al., 2021). Grant et al., 2021conducted a survey research and based on their results the eating habits of participants worsened as the intake of sweets and pastries increased. They also mention that the alcohol intake was increased while the consumption of red meat and sugary drinks decreased (Grant et al., 2021). Ismail et al., 2020 conducted research and the results state that the percentage of participants having 5 meals a day increased from 2.2 % to 6.2 % during pandemic and the percentage of participants skipping meals decreased from 64.4 % to 45.1 % before and during pandemic respectively. The increased sedentary time also increased snacking (sweet or salty ones) and decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables (Ismail et al., 2020). Based on Ramos-Padilla et al., 2021 more than half of the participants changed their mealtimes and women showed greater decrease in consumption of food compared to men (Ramos-Padilla et al., 2021). Study conducted by Dobrowolski et al., 2021 showed participants increase in alcohol consumption due to loneliness and also increase in consumption of tobacco (Dobrowolski & Włodarek, 2021). However studies conducted by other research groups showed no difference in consumption of alcohol (Chodkiewicz et al., 2020). The cited studies confirm our findings, as we did not observe a change in behavior in the area of eating during the pandemic measures and after their lifting.

Section of sleep

We found a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0381) in the time spent on sleep during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation. Ismail et al., 2020 state that the percentage of people who were sleeping more than 7 hours a day decreased and the percentage of participants who declared to have poor sleep quality increased. They also state that participants reported higher percentage of sleep disturbances during pandemic compared to pre pandemic-period (Ismail et al., 2020). Increased sleep disturbances and changes in sleeping habits also occurred in the research of Gupta & Pandi-Perumal, 2020; Franceschini et al., 2020; Cellini et al., 2020; Waerick-Silva et al., 2022; Gupta & Pandi-Perumal, 2020; Franceschini et al., 2020; Wearick-Silva et al., 2022 and Cellini et al., 2020). The cited studies correspond with our findings, as we observed a statistically significant difference in the time spent on sleep during the pandemic measures and after their lifting. Students spent less time sleeping during lockdown and strict pandemic measures. On the other hand, research conducted by Silva et al., 2021 found that 75% of women and 45 % of men reported no sleeping disturbances. The majority of participants aged more than 20 reported waking up later in the morning and the same was reported with age group of more than 60 years old in comparison with the data obtained before pandemic (Silva & Sobral, 2021).

Section of work

We did not find a statistically significant difference (p = 0.5146) in the time spent on work during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation. With the beginning of pandemic and application of numerous restrictions in order to prevent the spread of virus many organizations and corporates across the world found themselves in a position where employees had to rely on communication technologies to perform their jobs regardless of how technologically capable they were or what was their technical equipment at home. In US in February 2020 only 8.2 % of workforce worked fully from home, which changed toll May 2020 to 35.2 % fully working from home. It is also found that 71.1 % of employees that could effectively work from home did so in May 2020 (Hossain et al., 2023). Palumbo, 2020 concluded that telecommuting from home had a significant negative effect on work-life balance which was confirmed by several works of Hoffman, 2021, Sandoval-Reyes et al., 2021 or Zhang et al., 2021, where they mentioned that personal and work life interfered with one another more on days during which work was conducted remotely from home. (Palumbo, 2020; Hoffman, 2021; Sandoval-Reyes et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021) On the other hand, the research of Cannito & Scavarda, 2020 discovered that even though work-life balance may be negatively impacted by telecommuting, it may allow family members to participate in parental activities due to being in closer contact with the children. For example, some men claimed claimed that remote work has allowed them to be more involved as fathers. Working from home may be a possible way how to bring work-centric parents closer to their children and even make them to reorient their priorities (Cannito & Scavarda, 2020). The mentioned works do not confirm our findings, and we have not observed any change in work behavior during and after the pandemic measures. Students have been facing various problems related to depression anxiety, poor internet connectivity, and unfavorable study environment at home. Students from remote areas and marginalized sections mainly face enormous challenges for the study during this pandemic (Kapasia et. al., 2020). The work we conducted did not examine the impact of pandemic measures on the mental well-being of students, nor did it explore the financial and other burdens. Regarding the time spent studying, we did not observe a significant difference during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation.

Section of leisure time

There was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.5939) in time spent on leisure during and after the pandemic measures were lifted. Leisure time activities have also been significantly influenced by the introduction of anti-pandemic restrictions. According to study of Meier et al., 2021 participants intensively restricted their social contacts in their leisure time meaning that they obeyed introduced restriction of their governments. Based on their results the percentage of participants who introduced online communication technologies in their leisure time activities increased significantly compared to the period before pandemic. These findings are also consistent with findings of Gabbiadini et al., 2020 who reported more intense usage of communication technologies for performing voice calls or video calls. Participants in this study also reported performing leisure time activities together via online communication platforms like watching movies online or playing board games together, and activities like simple talking and spending time together, having drink or eating together were also shifted to online platforms (Meier et al., 2021; Cannito & Scavarda, 2020). Aymerich-Franch, 2020 and Panarese & Azzarita, 2021 concluced that in general the activities of respondents were connected with increased social media consumption, there was a growth in using streaming platforms as Netflix or using online communication channel as Whatsapp. In general, during lockdown people increased working and studying even during their free time, they spent more time cooking, watching movies, video calling, reading, doing physical exercise, cleaning and tidying their households (Aymerich-Franch, 2023; Panarese & Azzarita, 2021). The mentioned works confirm our proven findings, and we did not observe any change in leisure behavior during and after the pandemic measures. However, our conducted work did not address the changes that students made in their leisure activities.

Section of hygiene

We did not observe a statistically significant difference (p = 0.6744) in the time spent on hygiene during the pandemic measures and after their cancellation. Arai et al., 2021 conducted research based on hygiene practices of Japanese people and according to their findings almost 94 % of respondents declared wearing face mask when going out and more than 50 % of respondents reported increased handwashing frequency (Arai et al., 2021). Similar results have been achieved also by Głąbska et al., 2020 and S. R. Smith et al., 2022 where respondents declared significantly higher frequency of handwashing than before pandemics (Głabska et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2022). The mentioned works did not confirm our obtained data. We did not observe a statistically significant increase in the time spent on personal hygiene. However, this could have been influenced by the limited sensitivity of our research tool, as we did not focus on tracking individual hygiene activities. We assume that there may have been changes in hygiene habits, but overall, the time spent on hygiene did not significantly affect it.

Conclusion

According to our data, the behavior of natural science students in universities in Slovakia has changed mainly in the area of sleep, with students sleeping less. Furthermore, we found that the behavior of students did not differ significantly in the areas of sports, work, leisure, nutrition, and hygiene. This could be influenced by the small research sample, the predominance of female gender, and the sustainable habits that students have in these subjects. These findings provide a basic characterization of the behavior of natural science students at universities in Slovakia. In case of a repeated lockdown or worsened epidemiological situation, these findings can provide support to students as well as university educators. The presented work provides a basic overview of the time spent on basic activities and their changes during pandemic measures and after their cancellation. In case of a repeated worsening of the epidemiological situation and the implementation of pandemic measures, it would be appropriate to investigate not only the duration of the monitored sections but also their changes, changes in habits, differences in gender, age, place of residence, and more.

Reference

[1] Alhusseini, N. - Alqahtani, A. Covid-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Eating Habits in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Public Health Research. [online] jphr.2020.1868 , 9, 3. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2020.1868>.

[2] Anderson, J. C. - Gerbing, D. W. Predicting the performance of measures in a confirmatory factor analysis with a pretest assessment of their substantive validities. Journal of Applied Psychology. [online] 1991, 76, 5. 732–740 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.5.732>.

[3] Cellini, N. - Canale, N. - Mioni, G. - Costa, S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID‐19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Sleep Research. [online] 2020, 29, 4. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13074>.

[4] Ciotti, M. - Ciccozzi, M. - Terrinoni, A. - Jiang, W. C. - Wang, C. B. - Bernardini, S. The COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. [online] 2020, 57, 6. 365–388 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2020.1783198>.

[5] Deeks, S. G. - Overbaugh, J. - Phillips, A. - Buchbinder, S. HIV infection. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. [online] 2015, 1, 1. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.35>.

[6] Di Renzo, L. - Gualtieri, P. - Pivari, F. - Soldati, L. - Attinà, A. - Cinelli, G. - De Lorenzo, A. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine. [online] 2020, 18, 1. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5>.

[7] Dobrowolski, H. - Włodarek, D. Body Mass, Physical Activity and Eating Habits Changes during the First COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [online] 2021, 18, 11. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115682>.

[8] Donthu, N. - Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research. [online] 2020, 117. 284–289 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008>.

[9] Forshell, L. P. - Wierup, M. Salmonella contamination: a significant challenge to the global marketing of animal food products. Rev Sci Tech. 2006, 25, 2. P. 541-54.

[10] Franceschini, C. - Musetti, A. - Zenesini, C. - Palagini, L. - Scarpelli, S. - Quattropani, M. C. - Castelnuovo, G. Poor Sleep Quality and Its Consequences on Mental Health During the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology. [online] 2020, 11. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.574475>.

[11] Gabbiadini, A. - Baldissarri, C. - Durante, F. - Valtorta, R. R. - De Rosa, M. - Gallucci, M. Together apart: the mitigating role of digital communication technologies on negative affect during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in psychology. 2020, 11.

[12] Güner, H. R. - Hasanoğlu, İ. - Aktaş, F. COVID-19: Prevention and control measures in community. Turkish Journal of medical sciences. 2020, 50, 9. P. 571-577.

[13] Głąbska, D. - Skolmowska, D. - Guzek, D. Population-Based Study of the Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Hand Hygiene Behaviors—Polish Adolescents’ COVID-19 Experience (PLACE-19) Study. Sustainability. [online] 2020, 12, 12. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124930>.

[14] Grant, F. - Scalvedi, M. L. - Scognamiglio, U. - Turrini, A. - Rossi, L. Eating Habits during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: The Nutritional and Lifestyle Side Effects of the Pandemic. Nutrients. [online] 2021, 13, 7. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072279>.

[15] Gross, M. Pandemics past and present. Current Biology. [online] 2022, 32, 16. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.08.001>.

[16] Gupta, R. - Pandi-Perumal, S. R. COVID-Somnia: How the Pandemic Affects Sleep/Wake Regulation and How to Deal with it?. Sleep and Vigilance. [online] 2020, 4, 2. 51–53 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-020-00118-0>.

[17] Hoffman, C. L. The Experience of Teleworking with Dogs and Cats in the United States during COVID-19. Animals. [online] 2021, 11, 2. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020268>.

[18] Hu, D. - Liu, B. - Feng, L. - Ding, P. - Guo, X. - Wang, M. - Wang, L. Origins of the current seventh cholera pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [online] 2016, 113, 48. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1608732113>.

[19] Chodkiewicz, J. - Talarowska, M. - Miniszewska, J. - Nawrocka, N. - Bilinski, P. Alcohol Consumption Reported during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Initial Stage. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [online] 2020, 17, 13. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134677>.

[20] Christie, A. - Brooks, J. T. - Hicks, L. A. - Sauber-Schatz, E. K. - Yoder, J. S. - Honein, M. A. - Team, R. Guidance for implementing COVID-19 prevention strategies in the context of varying community transmission levels and vaccination coverage. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2021, 70, 30. 1044 p.

[21] Ifediora, O. F. - Aning, K. West Africa's Ebola pandemic: toward effective multilateral responses to health crises. Global Governance. 2017. P. 225-244.

[22] Kapasia, N. - Paul, P. - Roy, A. - Saha, J. - Zaveri, A. - Mallick, R. - Chouhan, P. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Children and Youth Services Review. [online] 2020. 116 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194>.

[23] Kaur, H. - Singh, T. - Arya, Y. K. - Mittal, S. Physical Fitness and Exercise During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Enquiry. Frontiers in Psychology. [online] 2020, 11. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590172>.

[24] Keshkar, S. - Dickson, G. - Ahonen, A. - Swart, K. - Addesa, F. - Epstein, A. - Murray, D. The Effects of Coronavirus Pandemic on the Sports Industry: An Update. Annals of Applied Sport Science. [online] 2021, 9, 1. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.29252/aassjournal.964>.

[25] Kielhofner, G. - Harlan, B. - Bauer, D. - Maurer, P. The Reliability of a Historical Interview With Physically Disabled Respondents. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. [online] 1986, 40, 8. 551–556 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.40.8.551>.

[26] Mashe, T. - Domman, D. - Tarupiwa, A. - Manangazira, P. - Phiri, I. - Masunda, K. - Weill, F. X. Highly Resistant Cholera Outbreak Strain in Zimbabwe. New England Journal of Medicine. [online] 2020, 383, 7. 687–689 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2004773>.

[27] Mascherini, G. - Catelan, D. - Pellegrini-Giampietro, D. E. - Petri, C. - Scaletti, C. - Gulisano, M. Changes in physical activity levels, eating habits and psychological well-being during the Italian COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: Impact of socio-demographic factors on the Florentine academic population. PLOS ONE. [online] 2021, 16, 5. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252395>.

[28] Meier, J. V. - Noel, J. A. - Kaspar, K. Alone Together: Computer-Mediated Communication in Leisure Time During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology. [online] 2021, 12. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.666655>.

[29] Mutz, M. - Gerke, M. Sport and exercise in times of self-quarantine: How Germans changed their behaviour at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. [online] 2020, 56, 3. 305–316 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220934335>.

[30] Palumbo, R. Let me go to the office! An investigation into the side effects of working from home on work-life balance. International Journal of Public Sector Management. [online] 2020, 33, 6/7. 771–790 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1108/ijpsm-06-2020-0150>.

[31] Panarese, P. - Azzarita, V. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Lifestyle: How Young people have Adapted Their Leisure and Routine during Lockdown in Italy. YOUNG. [online] 2021, 29, 4_suppl. 35–64 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/11033088211031389>.

[32] Pike, B. - Saylors, K. - Fair, J. - LeBreton, M. - Tamoufe, U. - Djoko, C. - Wolfe, N. The Origin and Prevention of Pandemics. Clinical Infectious Diseases. [online] 2010, 50, 12. 1636–1640 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1086/652860>.

[33] Piot, P. - Bartos, M. - Ghys, P. D. - Walker, N. - Schwartländer, B. The global impact of HIV/AIDS. Nature. [online] 2001, 410. 968–973 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1038/35073639>.

[34] Prokop, P. - Prokop, M. - Tunnicliffe, S. D. Is biology boring? Student attitudes toward biology. Journal of Biological Education. [online] 2007, 42, 1. 36–39 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2007.9656105>.

[35] Pinheiro, F. P. - Travassos, D. R. Oropouche virus. I. A review of clinical, epidemiological, and ecological findings. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. , 1981, 30, 1; Pt 1. P. 149-160.

[36] Ramos-Padilla, P. - Villavicencio-Barriga, V. D. - Cárdenas-Quintana, H. - Abril-Merizalde, L. - Solís-Manzano, A. - Carpio-Arias, T. V. Eating Habits and Sleep Quality during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adult Population of Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [online] 2021, 18, 7. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073606>.

[37] Raoult, D. - Mouffok, N. - Bitam, I. - Piarroux, R. - Drancourt, M. Plague: History and contemporary analysis. Journal of Infection. [online] 2013, 66, 1. 18–26 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2012.09.010>.

[38] Rai, N. K. - Ashok, A. - Akondi, B. R. Consequences of chemical impact of disinfectants: safe preventive measures against COVID-19. Critical reviews in toxicology. , 2020, 50, 6. P. 513-520.

[39] Sampath, S. - Khedr, A. - Qamar, S. - Tekin, A. - Singh, R. - Green, R. - Kashyap, R. Pandemics Throughout the History. Cureus. [online] 2021. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18136>.

[40] Sandoval-Reyes, J. - Idrovo-Carlier, S. - Duque-Oliva, E. J. Remote Work, Work Stress, and Work–Life during Pandemic Times: A Latin America Situation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [online] 2021, 18, 13. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137069>.

[41] Sánchez-Sánchez, E. - Ramírez-Vargas, G. - Avellaneda-López, Y. - Orellana-Pecino, J. I. - García-Marín, E. - Díaz-Jimenez, J. Eating Habits and Physical Activity of the Spanish Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Nutrients. [online] 2020, 12, 9. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092826>.

[42] Silva, E. P. - Sobral, S. R. Sleep Habits during COVID-19 Confinement: An Exploratory Analysis from Portugal. Informatics. [online] 2021, 8, 3. 51 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics8030051>.

[43] Smith, M. J. - Upshur, R. E. Ebola and Learning Lessons from Moral Failures: Who Cares about Ethics?: Table 1. Public Health Ethics. [online] 2015. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phv028>.

[44] Smith, S. R. - Hagger, M. S. - Keech, J. J. - Moyers, S. A. - Hamilton, K. Improving Hand Hygiene Behavior Using a Novel Theory-Based Intervention During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. [online] 2022, 56, 11. 1157–1173 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaac041>.

[45] Soriotulla, S Physical Education Class Management during COVID-19 Pandemic through ICT and it’s Complication. Journal of Advances in Sports and Physical Education. [online] 2023, 6, 1. 8–13 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.36348/jaspe.2023.v06i01.002>.

[46] Stephens, P. R. - Gottdenker, N. - Schatz, A. M. - Schmidt, J. P. - Drake, J. M. Characteristics of the 100 largest modern zoonotic disease outbreaks. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. [online] 2021. 376 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0535>.

[47] Scalera, N. M. - Mossad, S. B. he first pandemic of the 21st century: review of the 2009 pandemic variant influenza A (H1N1) virus. Postgraduate medicine. 2009, 121, 5. P. 43-47.

[48] Timpka, T. Sports Health During the SARS-Cov-2 Pandemic. Sports Medicine. [online] 2020, 50, 8. 1413–1416 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01288-7>.

[49] Trilla, A. - Trilla, G. - Daer, C. The 1918 “Spanish Flu” in Spain. Clinical Infectious Diseases. [online] 2008, 47, 5. 668–673 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1086/590567>.

[50] Usher, K. - Jackson, D. - Durkin, J. - Gyamfi, N. - Bhullar, N. Pandemic‐related behaviours and psychological outcomes; A rapid literature review to explain COVID‐19 behaviours. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. [online] 2020, 29, 6. 1018–1034 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12790>.

[51] Velavan, T. P. - Meyer, C. G. The COVID‐19 epidemic. Tropical Medicine International Health. [online] 2020, 25, 3. 278–280 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13383>.

[52] Wandersee, J. H. Plants or animals—which do junior high school students prefer to study?. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. [online] 1986, 23, 5. 415–426 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660230504>.

[53] Wearick-Silva, L. E. - Richter, S. A. - Viola, T. W. - Nunes, M. L. Sleep quality among parents and their children during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal De Pediatria. [online] 2022, 98, 3. 248–255 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2021.07.002>.

[54] Wolfe, N. D. - Dunavan, C. P. - Diamond, J. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature. [online] 2007, 447, 7142. 279–283 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05775>.

[55] Zhang, C. - Yu, M. C. - Marin, S. Exploring public sentiment on enforced remote work during COVID-19. Journal of Applied Psychology. [online] 2021, 106, 6. 797–810 p. Availiable at: <https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000933>.

Zpět na obsah / Back to content