| Ročník: 2013 | Volume: 2013 |

| Číslo: 2 | Issue: 2 |

| Vyšlo: 31. prosince 2013 | Published: December 31st, 2013 |

| Peng, Yan - Potměšilová, Petra - Potměšil, Miloň.

Primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education when working under the conditions of inclusion: an investigation in Olomouc Region of Czech Republic.

Paidagogos, [Actualized |

#28

Zpět na obsah / Back to content

Primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education when working under the conditions of inclusion: an investigation in Olomouc Region of Czech Republic

Abstrakt: The purpose of this study was to identify primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education when working under conditions of inclusion in Olomouc region of Czech Republic. The study was also designed to examine whether these teachers perceived themselves capable of implementing inclusive education in their regular classes and what support they most needed to help them carry out inclusive education in practice. The study mainly relied on quantitative methods. Questionnaire was designed to obtain needed data and was distributed to primary mainstream teachers involved in inclusive programs and working in 16 public basic schools (Grade 1 to 5) in Olomouc region. Analysis of data collected indicated these respondents’ attitudes toward current inclusive education seemed to be complicated: on one side, they did not completely admit the advantages of inclusive education; on the other side, they did not deny the benefits of segregated special settings; at the same time, they still kept neutral standpoints about if inclusive education could work well in practice. Also, they felt they were not capable of implementing inclusive education in their regular classes. All data seemed there were lots of difficulties which hindered carrying out “full” inclusive education in Olomouc region of Czech Republic.

Keywords: Inclusive education, primary mainstream school, teachers, attitudes, Olomouc region, Czech Republic

‘‘Inclusive - a word much more used in this century than in the last, it has to do with people and society valuing diversity and overcoming barriers” (Topping & Maloney, 2005, p.1). Inclusive education is one of the most important actual trends in theory and practice of education. One of the most important research questions related to inclusive education is what attitude the mainstream teachers have toward inclusive education?

A great deal of western research about related mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN indicated there was high correlation between inclusive education and the beliefs and attitudes of mainstream teachers (Hegarty, Pijl & Meijer, 1997; Villa & Thousand, 1995). Most of western research of attitudes toward inclusive education mainly discussed respondents’ perception for detailed components of inclusion of students with SEN. For example, Barnett and Monda (1998) had their investigation from following aspects: the extent of implementing inclusive education in school, the teachers’ expectation and preparation for inclusive education, the extent of community support, etc.; Cook, Semmel and Gerber (1999) emphasized the teacher’s responsibility and role, teacher’s skills of cooperative teaching, students’ academic improvement and so on. Lots of the research concluded that mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education was highly influenced by all kinds of teaching resources they could have (e.g. Salend & Duhaney, 1999). Also, some western studies showed whether mainstream teachers would have positive attitudes toward inclusive education depended on their educational background, teaching experience and related professional training (Center, Ward, Parmenter & Nash, 1985).

These findings confirmed the importance of mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN and revealed different mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN from different angles of views by different experts. Czech Republic has a long history of providing special education provision for children with SEN. It has made some progresses in inclusive education since Velvet Revolution in 1989 (Cerna, 1999). For to further realize the real status quo of Czech primary mainstream teachers’ (specially the primary mainstream teachers who working under conditions of inclusion) attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN, following research questions was the focus of this study:

- What was the primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes who involved in inclusive programs toward inclusive education in Olomouc Region of Czech Republic?

- Did they perceive they are capable of implementing inclusive education?

- What difficulties were they facing during implementing inclusive education in their regular classes?

Method

After reviewing relevant Western and Chinese literatures describing stakeholders’ (especially mainstream teachers’, parents’ and principals’) perceptions of and attitude toward inclusive education, mainly Deng’s research findings (2004), which revealed there were three principal components consisted of teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education: the advantages and disadvantages of inclusive education and the advantages of special school. In this Deng’s research, he concluded the three principle components specially could be used to test teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education in the countries or regions which began to implement inclusive education in initial stages (ibid). Considering Olomouc only systematically started inclusion-orientation education in 1990s (Cerna, 1999), author borrowed ideas from the Deng’s research outcomes and planed three principal components (Deng, 2004) to investigate respondents’ attitudes toward inclusion students with special educational needs. According to the research questions of this study, one draft of questionnaire were indentified and carefully worded and formatted by author for primary mainstream teachers involved in inclusive programs.

For to guarantee research validity and reliability, Author invited 3 international special education experts and 3 front line practitioners with at least 10 years experiences of implementing inclusive education in regular schools to review the draft and give suggestions. Minor changes in the wording and format of items of draft was made following these critical reviews. The final questionnaire was field-tested by using 30 primary mainstream teachers involved in inclusive programs in Olomouc region.

This questionnaire comprises 4 parts. An introductory statement was attached to declare the purpose and significance of this research and assurance of confidentiality in the first part. The second section was open-ended questions to elicit respondents’ background information. The third section used a 5-point Liker scale (strongly disagree, mildly disagree, not sure, mildly agree, strongly agree) format for items assessing respondents’ attitudes toward inclusive education. The last section designed one open question to ask for respondents to list three difficulties they were facing during implementing inclusive education in their regular classes. Totally, there were 23 items.

Sampling

According to research objects, the author implemented purposely sampling in Oloumouc region of Czech Republic. Three sample sites in this region, the City of Olomouc as urban site, the Town of Litovel and the town of Mohelnice as rural sites, were selected for investigation. And 16 regular basic public schools involved inclusive programs from the three sampling sites were selected to distribute questionnaire. The respondents must to be satisfied following conditions: firstly, they were teachers who were working in these 16 schools from grade 1 to grade 5; secondly, they were involving in their school’s inclusive programs; and lastly, there were at least one child with special educational needs learning in their regular classrooms. Author distributed 60 questionnaires to the object teachers in these 16 schools. As a result, 45 teachers from 16 regular basic public schools were surveyed; response rate was 75% and 38 questionnaires were available.

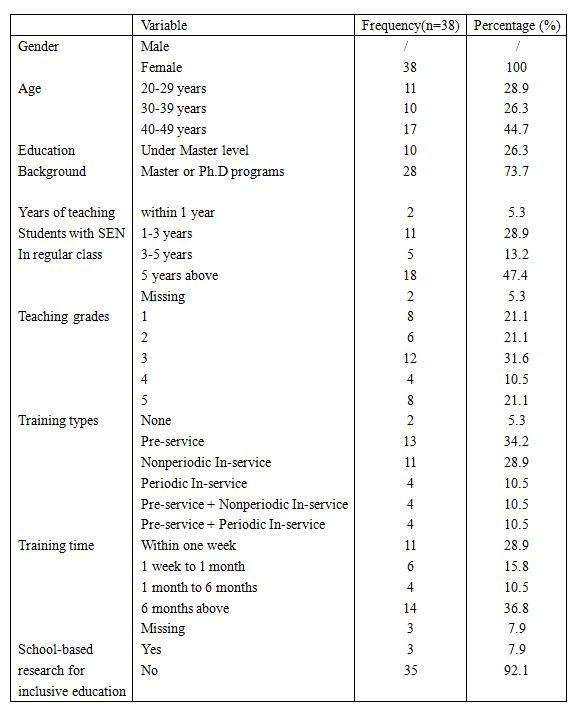

Table 1 showed demographic information of Czech teacher sample. This sample had a surprising high percentage of female respondents (100%). 44.7% of respondents were 40-49 years old. Majority (73.7%) of the total respondents received a master program education. About half (47.4%) of them reported that they had more than five years of teaching experience with students with SEN in regular classrooms. Majority (94.7%) of them reported that they had received certain training for inclusive education. Around half (47.3%) of respondents reported they received more than one month of training. Majority (92.1%) of these respondents had not done some school-based research for inclusive education.

Procedures of investigation

Firstly, authors contacted inclusive basic schools in Olomouc city, Litovel town and Mohelnice town and got the permissions to distribute questionnaires in these schools. And then, the authors conducted formal survey from school to school personally.

Data analysis

Data were coded and entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows (15.0) for statistical analysis. Analysis of the data was mainly conducted by using descriptive statistics.

Results

1. Results from closed questions of this questionnaire

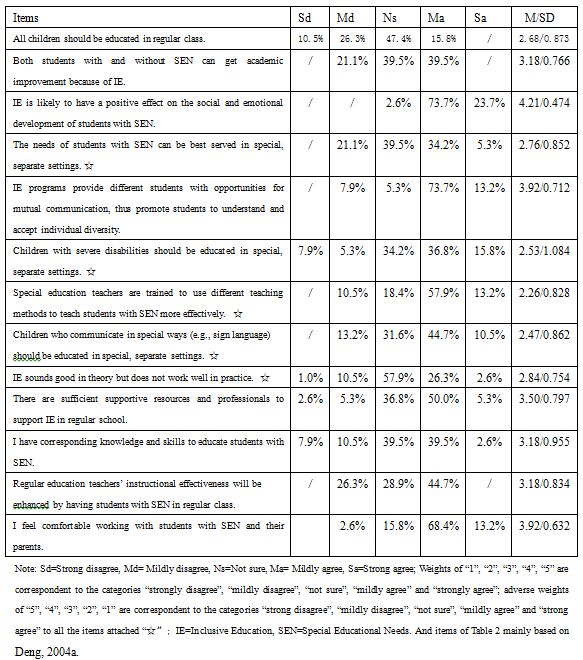

Table 2 showed only 15.8% of total respondents mildly agreed all children should be educated in regular class and 39.5% of them mildly agreed students with SEN could get academic improvement because of inclusive education. Majority (97.4%) agreed inclusive education could promote these students’ social and emotional development and 86.9% of them reported inclusive education promoted different students’ mutual communication, understanding and acceptance of individual diversity. 55.3% of them agreed there were sufficient supportive resources and professionals to support inclusive education in regular school. Less than half (42.1%) of respondents agreed they had corresponding knowledge and skills to educate student with SEN. 44.7% of them mildly agreed regular education teachers’ instructional effectiveness would be enhanced by implementing inclusive education in their regular classes. And majority (81.6%) of them agreed they felt comfortable working with students with SEN and their parents and it seemed there was no disputes on this point (M=3.92, SD=0.632).

Table 2 also showed 39.5% of the respondents agreed special, separate settings could best serve the needs of students with SEN. About half (52.6%) of them agreed that children with severe disabilities should be educated in special, separate settings but it seemed to be controversial (SD=1.084). 71.1% of them agreed special education teachers were trained to use different teaching methods to teach students with SEN more effectively than themselves and more than half (55.2%) of them also agreed that children communicating in special ways should be educated in special, separate settings at a large extent (SD=0.862).

And Table 2 showed 57.9% of the respondents expressed they were not sure if inclusive education sounded good in theory but did not work well in practice, mean score and standard deviation on this point also indicated respondents’ neutral attitude toward this opinion at a large extent (M=2.84, SD=0.754).

2. Result from open question of this questionnaire

At the last part of questionnaire, one open question was designed to ask these respondents to write down three major current difficulties they were facing during implementing inclusive education in their regular classes. 26 of them wrote down their viewpoints. On the whole, all difficulties were summarized as following from 26 responded teachers’ viewpoints written down the questionnaires:

“Regular schools are lacking financial support.”

69% of teachers who responded the open question focused on the problems related to financial support. Financial shortage seemed to be the most serious problem. They reported their schools lacked money to offer specific equipments, compensation aid and teaching and learning materials for students with SEN. And 85% of them mentioned the schools were short of money to hire teacher assistants too. 31% of them reported schools had no money to modify environment for students with SEN. Also, 35% of them reported they had overload work and the rewards were not enough to pay for their work for students with SEN.

“There are too many students in this classroom.”

High number of students in regular classroom seemed to be the second serious problem. 75% of the teachers who responded the open question reported this problem.

“I am not ready for inclusive teaching.”

24% of the teachers who responded open question mentioned they lacked professional preparation for inclusive education or they had some knowledge about special education, but it was not enough, e.g. one teacher (3.35% of them) reported she had some knowledge about students with learning difficulties, but had not knowledge about students with visual or hearing impairments. 31% of them still felt difficult to implement inclusive teaching which could not satisfy both typical students and students with SEN. Only 2 teachers (7.7% of them) could not accept inclusive education, e.g., one teacher (3.35% of them) reported students with mental retardation should go to special school not go to mainstream school.

“How to cooperate with experts?”

Teachers’ responses reflected following problems on this aspect: cooperation between experts and teachers was not sufficient; cooperation between experts and teachers was not good, e.g., there were 5 teachers (19% of the teachers who responded the open question) reported experts of SPC had no interests to go to mainstream schools though they had to visit these schools once a year.

“How to cooperate with family?”

There were 6 teachers (23% of the teachers who responded the open question) reported there were some problems to cooperate with families of children with SEN. Psychological support from psychologists and social workers is needed.

“Whole education system is not ready for inclusive education.”

One teacher “pointed out” (3.35% of the teachers who responded the open question): “inclusive education need full cooperation and willingness of related organizations, and it’s really hard to carry out”. Another teacher “said”: “I think the order of implementing inclusive is wrong. The right order is that regular schools should have already prepared everything for inclusion, after that, students with SEN can go to regular school, in fact, now the order has been inverted, students with SEN have gone to regular schools but regular schools have not been ready for including them at all”. Another teacher (3.35% of the teachers who responded the open question) reported that officials were reluctant to solve problems for inclusive education. And there were 4 teachers (15.4% of the teachers who responded the open question) reported the school administrators did not support inclusive education or paid much attention to it.

Summary of results

Analysis of data collected indicated these respondents’ attitudes toward current inclusive education seemed to be complicated: on one side, they did not completely admit the advantages of inclusive education; on the other side, they did not deny the benefits of segregated special settings; at the same time, they still kept neutral standpoints about if inclusive education could work well in practice. Also, they felt they were not capable of implementing inclusive education in their regular classrooms though they had experienced certain pre-service and in-service professional training for inclusive education. Most of them reflected current inclusive education strongly needed more financial support and they really wanted to receive more effective professional training, and skills and knowledge of cooperation with inclusive experts and families of children with SEN for further inclusive practice.

Discussion

Why did the investigated primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN seem to be complicated? I guess this complicated attitude was the reflection of Czech inclusive education.

Firstly, only 42.1% of surveyed teachers agreed they had corresponding knowledge and skills to implement inclusive teaching, there were 39.5% respondents were not sure and 18.4% disagreed. Also, Potměšil (2011) found about a half of surveyed educators working under conditions of inclusion reported their concerns about lack of professional competencies and support and effectiveness of such educational work in his recent research. Because lacking of sufficient professional confidence, teachers still had some doubts about meaning, methods and outcomes of inclusion.

Statistics indicated majority of investigated teachers could get pre-service and in-service training for special needs education as Act on education staff (Parliament of Czech Republic, 2004) stipulated and they could get specialists’ guidance for inclusive teaching. But why statistics still showed they were not sure if they had corresponding knowledge and skills to carry out inclusive teaching? And they did not agree inclusion could enhance their teaching effectiveness? Also, some of them reported they really did not know how to deal with difficulties of teaching students with SEN and they had not corresponding professional preparation even they really experienced some training for special needs education. For to explain this contradiction, it seemed we should doubt the quality of current Czech teacher training for inclusive education whatever pre-service or in-service.

In addition, statistics showed respondents seldom did some school-based research for inclusive education. School-based research is an effective approach to promote teacher’s professional development (UNESCO, 2001); it can enhance teacher’s reflective ability which will radically promote teacher’s professional development. Observing other teachers’ inclusive practice is another rapid and effective approach to promote teacher’s professional development too. The principle of learning by doing should be really taken into account and paid more attention by university educators and school administrators for teacher preparation and training.

Secondly, current mainstream schools still have not good capability to accept students with severe or profound disabilities, even for students with mild disabilities; one of responded teacher pointed out regular schools were not ready for these students. As we know Czech Republic has a long history for developing segregated special education, relative matured, sound and well-equipped special schools still have their active effects on providing educational service for students with SEN until now.

The problem with a size of class here is based on financial situation of each school. On one side there is a legal frame for decreasing of the pupil’s number when even just one student with SEN is included, but money reason eliminates such possibility.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the investigated teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN seemed to be complicated, it seemed like these teachers saw a positive impact on social development and understanding of diversity, but at the same time saw practical challenges too. All the collected data showed that it is not possible to reach the goal of full inclusion in Czech public schools now. How to further improve quality of teachers training and how to promote teachers’ professional development for inclusion should be placed on central and local government and school’s agenda. It also appeared that reducing teacher work load, enhancing financial support, improving cooperation between regular education teachers and special education experts should be further considered. Results of this research will bring a feedback for Teacher training colleges to make some modifications of their study programs as well as prepare some offer for teachers lifelong learning - special courses.

Important results from an international research were brought by Sharma et. all. (2006). On the area of several countries have been shown, that emotional and social reflection focused on inclusive education is high but teaching skills and class managing competences are still evaluated as low, unsatisfactory. Described research in Czech and its results are at comparable level.

Limitation of this research

Firstly, this is the first time that foreigner researcher and Czech researcher carried out investigation about primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN in Olomouc region of Czech Republic together. Our sampling was limited to primary mainstream teachers involved in inclusive programs in 16 regular public primary schools in Olomouc city, Litovel town and Mohelnice town. It is unknown whether the characteristics of respondents from these regions might be shared by samples from other regions.

Secondly, few literatures of inclusive education, especially mainstream teachers attitudes toward inclusion of students with SEN in Czech Republic were published in English, which limited authors’ understanding and exploration of investigated results, the discussions about our research topic was also limited.

This article is one of outcomes of An Important Scientific Research Project funded by Sichuan Normal University (2010-2012), People’s Republic of China. At the same time, this research also is funded by the Key Research Project of Sichuan Province Department of Education People’s Republic of China (2012-2014, 12SA080). The research project was also founded by IGA Palacký University Olomouc - PdF_2011_005 end CMTF_2013_007 Czech Republic.

Attachements

(1) Questionnaire of mainstream primary school teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education

Reference

[1] Barnett, C. - Monda-Amaya, L.E. Principles’ knowledge and attitudes toward inclusion. Remedial and special education. 1998, 3. P. 181-192.

[2] Center, Y. - Ward, J. - Parmenter, T. - Nash, R. Principals’ attitudes toward the integration of disabled children into regular schools. The Exceptional Child. 1985, 32. P. 149-161.

[3] Cerna, Marie. Issue of inclusive education in the Czech Republic – a system in change. Harry, Daniels. - Garner,Philip.(eds.). Inclusive education. Routledge, 1999.

[4] Cook, B.G. - Semmel, M.I. - Gerber, M.M. Attitudes of principals and special education teachers toward the inclusion of students with disabilities: critical differences of opinion. Remedial and Special Education. 1999, 20. P. 199-207.

[5] Deng, M. - The comparative study between rural and urban primary schools on teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. Educational Research and Experimen. 2004, 1. P. 61-66.

[6] Hegarty, S. - Pijl, S. J. - Meijer, C. J. Inclusive Education: A Global Agenda. London: Routledge, 1997.

[7] Parliament of Czech Republic he Act on Education Staff. Retrieved April 11. [online], [Cited ] 2004. Availiable at: <http://www.msmt.cz/areas-of-work/act-no-563-the-act-on-pedagogical-staff>.

[8] Potměšil, M. - The sentiments, attitudes and concerns of educators when working under the conditions of inclusion. Annales Universitatis Paedagogica Cracoviensis (Studia Psychologica VI). 2011. P. 71-84.

[9] Salend, S.J. - Duhaney, G. The impact of inclusion on students with and without disabilities and their teachers. Remedial and special education. 1999, 2. P. 114-126.

[10] Sharma,U. - Forlin,Ch. - Loreman,T. - Earle,Ch. Pre-service teachers’ attitudes, concerns and sentiments about inclusive education: an international comparison of novice pre-service teachers. International journal of special education. 2006, 21, 2. P. 80-94. ISSN .

[11] Topping, K. - Maloney, S. (eds.). The RoutledgeFalmer Reader in Inclusive Education. New York NY: RoutledgeFalmer, 2005. p. ISBN 0-415-33664-3.

[12] UNESCO. Open file on inclusive education: support materials for managers and administrators. Paris, 2001.

[13] Villa, R.A. - Thousand, J.S. Creating an inclusive school. USA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1995. p. ISBN .

Zpět na obsah / Back to content