| Ročník: 2019 | Volume: 2019 |

| Číslo: 2 | Issue: 2 |

| Vyšlo: 21. prosince 2019 | Published: December 21st, 2019 |

| Pecková , Simona.

Do Contemporary Business English Textbooks Develop Students’ Indirect Language Learning Strategies?.

Paidagogos, [Actualized |

#8

Zpět na obsah / Back to content

Do Contemporary Business English Textbooks Develop Students’ Indirect Language Learning Strategies?

Abstract: In this paper, we map the extent to which textbooks of business English vocabulary and skills support the development of indirect learning strategies. For our survey we adopted the classification of learning strategies developed by Rebecca Oxford. Inasmuch as direct strategies (memory, cognitive, compensation) of language learning are an essential part of every textbook, we have focused on indirect strategies (metacognitive, social, affective). We have selected the most frequently used textbooks of business English vocabulary and business English skills. In our analysis, we have tried to detect any activities in textbooks that could help learners to develop the usage of indirect learning strategies. We have found that except for two textbooks of the series (English communication skills published by DELTA Business Communication Skills and the series published by Macmillan), the focus is only on language content. To be more specific, many of the textbooks contain activities designed for pair work or group work (and thus they support social learning strategies), but most of the authors of these textbooks do not develop metacognitive and affective learning strategies for students. In conclusion, we recommend that in the future authors take into account the importance of emotions and self-awareness in the learning process and incorporate activities focused on these areas into their textbooks.

Keywords: Language learning strategies, learner autonomy, lifelong learning, textbook analysis, business English vocabulary and skills, language for specific purposes.

Introduction

One of the typical features at the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century is the globalisation of the world. Globalisation is an important factor in the methodology of foreign languages. The need for an international exchange of information is like a trigger for communication in an international language. As the state of knowledge continues to develop, language learning becomes a lifelong process as well as a necessity for society as a whole.

Moreover, the quickly changing nature of the contemporary world, where one has to be ready to react to changes (e.g. changes in the labour market), is another reason for the implementation of the lifelong learning concept. Lifelong learning is one of the pillars of the EU education policy.

In the second half of the 20th century, there was an important change in the paradigm of pedagogy. Attention shifted from the teacher to the students, to their capacities, needs, learning styles, etc. This shift of attention has involved a change in the teacher’s role: The teacher is not here only to transfer information, rather to act as the student’s partner in the learning process, a facilitator of the process, the student’s coach.

The second half of the 20th century was also a time of redirection from behavioural to cognitive psychology. Psychologists are no longer interested only in the behaviour of people; they are trying to understand the way humans think. It is thanks to the findings of cognitive psychology that we can understand the learning process better. The fact that someone is being taught does not necessarily mean that they will learn anything. Every teacher notices that even though their students are exposed to the same teaching (they are taught by the same teacher, they work with the same materials, they receive the same content, etc.), each of them achieves a different result and has a different attitude towards the subject. Every student has (was born with or has developed during the first years of their life) their own specific features: they have different intellectual potential, a different amount and type of motivation, their own learning style. In addition, another important factor of the learning process are the emotions experienced by every student during the learning process. Some of the factors of successful learning cannot be influenced (e.g. intelligence, talent for languages, family background, etc.), whereas others like type and amount of motivation, study skills, etc., can. Teachers and the authors of textbooks and other study materials can help students develop their learning strategies and study skills in general.

In this paper, we are going to focus on textbooks of business English vocabulary and business English skills. We will analyse if and how far contemporary textbooks of business language help students acquire and develop indirect learning strategies. We have decided to focus on business language, as this is a kind of LSP (language for specific purposes) usually studied by adult people or young adults at colleges and universities who are able to develop their study strategies and intrinsic motivation and who are already able to control their own learning, etc.

Language Learning Strategies

Language learning strategies could be defined as ‘steps taken by students to enhance their own learning’ (Oxford, 1990). The same author says that language learning strategies are tools for active, self-directed involvement, which is essential for developing communicative competence. She enumerates the features of language learning strategies as follows: Language learning strategies contribute to the main goal of communicative competence and allow learners to become more self-confident. They also expand the role of teachers. Furthermore, language learning strategies are problem-oriented. They are specific actions taken by the learner that involve many aspects, and not just the cognitive, and they support learning both directly and indirectly. They are not always observable and often dwell in the subconscious. Language learning strategies can be taught, they are flexible and are influenced by a variety of factors.

Other authors (Lojová, Vlčková, 2011) say that language learning strategies can be conscious or subconscious procedures that the learner uses to facilitate the acquisition, processing, memorising, retrieval and application of information.

The concept of learning strategies started to be elaborated in the 1960s thanks to the development of cognitive psychology (Carton 1966, Stern 1975, Rubin 1981). One of the most frequently used classifications of learning strategies was created by Rebecca Oxford (1990). Later, a whole method of implementing language learning strategies training into language courses was developed (Ellis, G., Sinclair, B., 1989 or Chamot, O’Malley, 1994 or Dexter, Sheerin, 1999). Since then, research has been carried out on language learning strategies, often with contradictory results. Several research tools have been developed (Cohen, Oxford 2002). In the Czech Republic, the country of origin of the author of this text, the concept was described and further developed by Lojová and Vlčková of Masaryk University in Brno. These two language teachers and researchers in the area of pedagogy emphasise the difference between learning styles (innate) and learning strategies (acquired and developed). There are other authors who deal with the same or similar issues but do not explicitly call them ‘learning strategies’ (e.g. Petty, 1999, Janíková 2011, etc.). Interestingly, these ideas were already anticipated in the 17th century by the father of pedagogy and modern education, John Amos Comenius (1658). When he speaks about the basic principles of good teaching, he says that ‘learning has to be fast, nice and permanent’ or that ‘the learner’s task is to work, whereas the teacher’s task is to manage’.

We have already implied that EU educational policy recognises the importance of learner autonomy. European Language Portfolio is a website as well as a series of booklets developed by the Council of Europe to allow its users to record their language learning achievements. It could be considered as a tool for fostering language learning strategies, namely the metacognitive strategy.

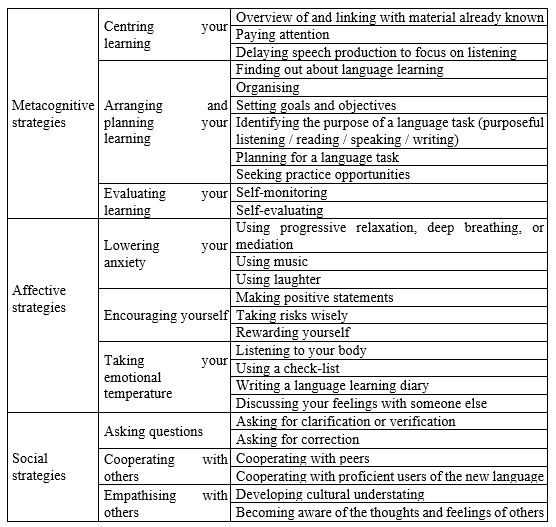

As we have already said, several classifications of learning strategies have been designed so far. We will adopt the one developed by R. Oxford (1990), who divides these strategies into two broad categories: direct (primary) and indirect (secondary) strategies of learning. The direct strategies are further divided into memory, cognitive, compensatory. The indirect strategies are categorised as metacognitive, social, and affective.

Use of learning strategies is a predictor and determinant of the results of the learning process. But at the same time, the ability to use learning strategies is also one of the goals of education. The relationship between learning strategies and study results is often a reciprocal one.

Learner autonomy is an area of interest of many widely respected authors. For example, Cuq (2005) says that one of the goals of foreign language instruction is the autonomy of the student, i.e. the gradual weakening of the teacher’s dominant role. He refers to another French author, Henri Holec (1992), who says that ‘autonomy can only be learnt’ and so that, in addition to transferring knowledge and communication skills, one of the duties of the teacher is to ‘create good students’. Helping students acquire learning strategies is one of the ways to increase the efficiency of the learning process.

We agree with the above authors. It is necessary to help students become responsible for their own lives, to be autonomous as learners and to take a proactive approach towards their future careers. There is a very narrow connection between learning strategies and other recent pedagogical issues, such as self-regulated learning or learner autonomy, both of which could be considered benefits of the acquisition of learning strategies. Self-regulated learning (SRL) is a cyclical process, wherein the student plans for a task, monitors their performance, and then reflects on the outcome (Zimmerman, 2002).

If we talk about the methodology of foreign languages, it is also important to mention the goals of foreign language instruction. Hendrich (1988) distinguishes three of them: communication, didactics and personal growth. The most important goal of foreign language instruction is communicating in the given language. Today, our aim is to help students understand and be understood. Certain errors that do not make comprehension impossible are generally acceptable. The ability to communicate in a foreign language presupposes the acquisition of all four language skills (listening comprehension, speaking, reading comprehension and writing) and sufficient knowledge of language systems (grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation and orthography). The didactic goal is then connected to the acquisition of the language itself, as well as to becoming acquainted with the history, culture, geography, etc., of the given language areas. Learning and acquiring a foreign language can also be a means of personal growth. It fosters self-discipline, responsibility, stamina, etc., in students. Furthermore, it develops both short-term and long-term memory, logical thinking, learning strategies, etc. Even though communication is the most important goal of language instruction, all three goals complement each other.

To get a keen understanding of the problem, it is necessary to say a couple of words about motivation and its importance in the process of learning foreign languages. A Czech theoretician of education, Průcha (2009), defines motivation as the result of external and internal factors that trigger human behaviour, then direct and maintain it. There are two types of motivation: extrinsic (coming from teachers, parents, etc.) and intrinsic (coming from the learners themselves).

We know that learning motivation is of a changing nature – it can both grow and become weaker. In such case we may speak about demotivation, which may be caused by repeated failures. Based on these facts, we may conclude that positive emotions during the learning process are very important to the development of student motivation and to the efficiency of the learning process. Communication in a foreign language within a practice enterprise enables students to experience the feeling of success, which is a very important ‘springboard’ and helps create a positive attitude towards foreign languages.

Rogers (2002) says that intrinsic motivation prevails within adult people, while children mostly have to be motivated from the outside. He also claims that intrinsic motivation is of a long-term nature: a person with developed intrinsic motivation can overcome obstacles more easily and is able to persist in their efforts.

The task of the teacher nowadays is thus not only to transfer knowledge, but also to cultivate intrinsic motivation in their students and support their proactive approach to work, to help them become autonomous and responsible for their own lives. Students who enjoy intrinsic motivation are able to direct their own learning (i.e. they are capable of self-regulated learning). They are able to plan their future activities, to set their goals, manage the time they have or overcome possible obstacles or failures. It is thus very important to develop perspective orientation in students.

The acquisition of language learning strategies is a perquisite of learner autonomy and self-regulated learning, the latter being defined as a kind of learning where the learner becomes an active participant of their own learning (Průcha, 2009). In such case, as learners develop intrinsic motivation towards learning, they organise the learning activities for themselves, they understand the learning process, and they can evaluate their own progress and make plans for their learning activities in the future. Autonomy in learning is important for lifelong learning.

In this paper, we map the extent to which textbooks of business English support the development of indirect learning strategies. Business English is a kind of LSP – i.e. language for specific purposes. Hutchinson (1987) describes the origins and the current situation of the methodology of language for specific purposes. The interest in languages for specific purposes originated after the Second World War. At that time, the enormous development of science and international trade triggered the demand for an international language. It was due to the economic power of the United States of America that English took on this role. There was a new generation of extremely motivated people who realised that if they were to be successful in their professional life, they would have to speak English. They included businessmen who wanted to sell their products abroad, scientists who wanted to keep up with advances in their disciplines, and students who needed to read books that were available only in English.

We deal with LSP when we want to communicate a specific content in a foreign language.

Some of the specific features of LSP are precise organisation (the logical structure of the text and coherence) and the careful selection of grammatical and lexical means (Hendrich, 1988). Ambiguities are unthinkable in this regard. The scope of the specific content and the content itself have to correspond to the aims of the course and to the language level and age of the students. Integrating specific content into the curriculum can have a very motivating effect.

Carras (2007) summarises the specific features of the methodology of languages for specific purposes, as opposed to a general language. He says that such instruction is organised on the basis of a specific demand. The client (student or more often the organisation the student works for) usually has clearly defined needs and requirements. For example, they want to penetrate a foreign market and so need their employees to be able to communicate at work in English. These students are specialists in a certain field. Very often they form heterogeneous groups where each of them has a different level of English, different ages and different learning styles. But they all have the same aim of learning. Typically, these students have limited time possibilities. The teacher’s preparation and the teaching itself require specific techniques.

Courses and textbooks of language for specific purposes are generally designed for adult students or late teens who have already acquired (often unconsciously) some of the learning strategies or they are able to acquire and use them.

Material and Methods

A considerable amount of research on language learning strategies has already been done in the world: Han (2012), Cavana (2012), Bertolotti (2016), Zhoc et al. (2018), Robson (2016), Thoutenfood (2013), Chamot (2005), etc.

Some of the research results (Vlčková, Bradová 2014), however, challenge the idea of the effectiveness of using learning strategies. According to Vlčková, the problem lies in the fact that it is very difficult to ‘measure’ the extent to which students use these strategies in the learning process. Furthermore, there is often a contradiction between what students claim to use and what they really use in the learning process (Vlčková, 2014). It is a well-known fact that research of a causal nature is problematic in general. Educational reality is an area which is changing constantly and where many factors operate at the same time. It is thus difficult to trace the causal relationships between individual phenomena. That is why it is often necessary to accompany a quantitative approach with a qualitative one that can provide us with an explanation of the data received from quantitative surveys.

In our work we have used the qualitative approach. The method is content analysis. We analysed several textbooks of business English vocabulary and communication skills currently available on the Czech market (i.e. the country of origin of the author of this article). Most of the books were published by a publisher in an English-speaking country (UK, USA), but we also included a textbook published in the Czech Republic. Altogether we managed to gather and to analyse six different series of textbooks: Cambridge University Press (I), DELTA Business Communication Skills (II), Oxford University Press (III), Market Leader (IV), Fraus series (V), Macmillan series (VI).

We have analysed books that solely focus on the development of business English vocabulary and business English skills. Conversely, we have left aside textbooks designed for general courses of business English, such as International Express, Business Benchmark, etc.

We analysed all the chapters of the given textbooks (the chapters generally had identical structures).

Direct strategies (memory, cognitive, compensatory) are naturally a part of any textbook. Illustrations and graphical highlighting can be classified as memory strategies. Numerous exercises are a case of cognitive strategies, whilst putting new vocabulary into context is a case of compensatory strategies.

We are thus especially interested in indirect language learning strategies (metacognitive, affective, social) and their occurrence in textbooks of business English.

In our survey we try to find answers to the following questions:

- Metacognitive strategy: Do the authors explicitly teach students how to learn? If so, how? (i.e. do they help students develop metacognitive strategies?)

- Affective strategy: Do the authors of the textbooks give teachers or students any suggestions on how to reduce stress within the learning process? Do they help teachers or students work effectively with their emotions during the process of learning? (i.e. do they help students develop affective strategies?)

- Social strategy: Do the authors of the textbooks invite students to cooperate with each other? Do they recommend students ask their teachers (or other more experienced speakers of the given language or native speakers) for clarification or for correction of their mistakes? (i.e. do they help students develop social strategies?)

Results and Discussion

I. The business vocabulary series ‘In Use’

- Metacognitive strategy: No activities or suggestions aimed at developing a metacognitive learning strategy for students (no suggestions on how to raise their awareness of learning, no tips on how to organise the learning process, how to set goals, etc.)

- Affective strategy: Occasionally the textbooks of the series include some humorous content, which could be considered a means on how to support the creation of positive emotions during the learning process. However, there were no other activities or suggestions aimed at developing students’ affective strategy of learning (no tips on how to reduce the amount of stress or anxiety possibly produced by learning, no suggestions on relaxation techniques, etc.)

- Social strategy: Questions for discussion in the introduction of each chapter – pair work or group work. At the end of each chapter, there were ideas for reflection or discussion called ‘Over to you’. However, there were no recommendations to students on how to make the most of the communication of native or proficient speakers of English (asking for correction, for repetition or verification, etc.).

II. Books on developing business English communication skills published by DELTA Business Communication Skills:

We consider this series of business English skills to be the best form of indirect learning strategies development.

- Metacognitive strategy: At the beginning of each series of the books, there is a needs analysis to help students think about their strengths and weaknesses in that particular area of English. They are then prompted to identify and prioritise their immediate and future needs in that area. Before students start working on the individual chapters of the book, they are also familiarised with the so-called ‘Learning journal’ (preceding the first chapter), to which they are asked to refer at the end of each core unit. The aim of the learning journal is for students to summarise helpful examples of language and tips on improving their skills in the given area (negotiating, telephoning, meetings, socialising, emailing – all the textbooks have the same structure). Another kind of awareness-raising activity in this series of textbooks is the students also evaluate each other’s performance and recommend to each other areas they should focus on. Following the learning journal is a section where students are recommended to reflect on and take note of specific steps they need to do in order to overcome a certain difficulty. They are given tips on their effective performance in business and helpful suggestions for language study.

- Affective strategy: Students are advised to set realistic objectives and deadlines in order to avoid an excessive amount of stress which sometimes occurs during the learning process.

- Social strategy: Students are advised to discuss their strengths and weaknesses in English with their colleagues in the course and to recommend to each other which areas they should focus on in order to make improvements.

III. Books developing business English communication skills published by Oxford University Press

Each of the books from the series includes a Teacher’s book.

- Metacognitive strategy: We have not detected any activities developing learners’ metacognitive strategies.

- Affective strategy: Occasional humorous illustrations

- Social strategy: Pair work, group work. In the Teacher’s book, the teacher is advised to encourage students to discuss and evaluate each other’s presentations and to provide feedback to each other.

IV. Market Leader series:

- Metacognitive strategy: We have not detected any activities developing learners’ metacognitive strategies.

- Affective strategy: We have not detected any activities developing learners’ affective strategies.

- Social strategy: Questions for discussion in the introduction of each chapter – pair work or group work. At the end of each chapter, there are ideas for reflection or discussion called ‘Over to you’.

V. ‘Fraus’ series from a Czech publisher (adapted from German authors):

- Metacognitive strategy: We have not detected any activities developing learners’ metacognitive strategies.

- Affective strategy: We have not detected any activities developing learners’ affective strategies.

- Social strategy: Pair work, group work

VI. Series from Macmillan:

Each of the books in the series is organised in a slightly different way. That is why we are going to comment on the books separately (A – D).

A. Email English

- Metacognitive strategy: We have not detected any activities developing learners’ metacognitive strategies.

- Affective strategy: Pair work and group work is advised here as a possible way to create a good atmosphere in the class and thus a way on how to reduce anxiety.

- Social strategy: In the introduction of the book, students are encouraged to get feedback on the emails that they write in real life: ‘If you know a friend whose English is better than yours, or a native speaker, then ask them to make comments on your writing. Also, study the English in the emails you receive. If you receive a well-written email, remember to look carefully at the language. Build your own phrase book: start your own bank of phrases from ones you have received in an email or ones you have written yourself.’ The textbook is not accompanied by a Teacher’s book. There is only a two-page introductory section entitled ‘To the teacher’ where teachers get a couple of ideas on how to proceed through the material. The teacher here is advised, for example, to encourage peer correction.

B. Networking in English:

- Metacognitive strategy: The book is introduced with a part called ‘needs analysis’ where the students are first asked to go through ten statements mapping their strong and weak points in English as well as their needs. Based on the results of this part, students are advised on how to work with the textbook and which chapters should be given priority. We find this introductory part particularly useful, as it raises the students’ awareness of their own learning, which is key to the good use of metacognitive learning strategies. Moreover, each chapter concludes with a section called ‘Social planner’, where students are encouraged to make a plan for improvement in the given area and to personalise the newly acquired language.

- Affective strategy: Occasionally there are some tips on how to make networking conversation more relaxed, such as using jokes or just smiling. These recommendations are often accompanied by noticing that jokes and other ice-breakers are often culturally specific.

- Social strategy: As the book focuses on networking, there are naturally suggestions for many oral activities done in pairs or groups.

C. Telephone English:

- Metacognitive strategy: Readers of this book are recommended to prepare for phone calls – to make notes on what they want to say before they call and to write the key phrases down to be sure they will say them correctly.

- Affective strategy: Occasional humorous illustrations.

- Social strategy: In the introductory part of the book called ‘To the student’, students are encouraged not to be afraid to ask callers to repeat themselves if they speak too quickly. They are also recommended to note down any interesting and useful expressions they might hear from a proficient or native speaker of English. Of course, as it is a textbook of telephoning, many of the proposed activities will be done as pair work.

D. Presentations in English:

- Metacognitive strategy: Activities aimed at developing a person’s metacognitive strategies are particularly well elaborated in this textbook. At the beginning students are advised to keep a journal reflecting their goals when it comes to presentation skills in English and the extent to which these are achieved. Students are prompted to think about the way presentation skills are acquired.

- Affective strategy: Again, it is obvious that the author of this textbook is not only a teacher of English, but also a professional trainer and coach of presentation skills. Although there are several activities focused on the English vocabulary and grammar structures that one needs to know in order to be able to give presentations in English, the main interest of the textbook lies in the non-linguistic skills that the presenter needs to develop. Students are reassured that it is normal to feel nervous before or during a presentation. The author of this textbook helps learners to understand the emotions related to speaking in public, to accept and work with these emotions.

- Social strategy: When giving a presentation within this course, students are advised to make a record of these presentations in order to analyse it together at a later time. Students are encouraged to learn to provide and accept feedback from others.

Conclusions

Having analysed the most frequently used textbooks of business English, we can say that even though these textbooks are well elaborated in terms of the content of business language, most of them do not systematically help students develop indirect strategies of learning. Some of the textbooks contain no or very few activities fostering the development of language learning strategies. Sometimes there are at least a few tips on effective learning in the teacher’s manual or in the introductory text of the textbook. Some authors provide practical suggestions for teachers on how to train their students to become more successful language learners.

We can conclude that, in terms of helping students develop their study skills, the best are DELTA Business Communication Skills and the series published by Macmillan. In the first case, the authors have integrated a learning journal that encourages students to think about their own learning process, to set goals, reflect on how these goals have been fulfilled and consequently plan an effective learning process. In other words, the DELTA Business Communication Skills series is very well designed, particularly in the development of metacognitive learning strategies.

In the series published by Macmillan (emails, presentations, networking, telephoning) there is also emphasis put on the development of affective learning strategies. Especially in the case of Presentations in English, the authors have realised that no matter how well the language component is done, learners will not become successful presenters if they do not learn to work with their emotions.

Having considered the importance of activities fostering the acquisition and development of indirect strategies, we think that they should be automatically integrated into any textbook of a foreign language (and perhaps not only into textbooks of languages).

Ideally, pre-service teachers should be trained in methods on how to develop the learning strategies of students. Alternatively, investments in lifelong learning would enable further training of in-service teachers.

It is important not to forget that the results of such training may not be evident immediately. It takes time to personalise one’s skills and so quick results cannot be expected.

As far as further research is concerned, it would be useful to analyse other kinds of language textbooks (and perhaps not only textbooks of foreign languages) in order to get an overall picture of the integration of learning strategies into study materials. Subsequently, sharing the results and conclusions of such surveys would help gradually improve the awareness of indirect learning strategies among teachers and textbook authors.

There is an ancient proverb that says, ‘Give a man a fish and he eats for a day. Teach him how to fish and he eats for a lifetime’. The same principle applies to language teaching and learning. If we, teachers, teach students how to use the past simple in English, they will probably pass a test on it. If we teach them how to learn, i.e. how to manage their own learning, how to set goals, cope with stress and anxiety within the learning process, benefit from cooperation with others, etc., there is a chance that we will create good learners. We have a unique opportunity to contribute to the growth of autonomous people able to take responsibility for their own lives.

Reference

[1] Ainscough, L. et al. Learning hindrances and self-regulated learning strategies reported by undergraduate students: identifying characteristics of resilient students. Studies in Higher Education. 2018, 43, 12. P. 2194-2209.

[2] Bertolotti, G. - Beseghi, M. From the learning diary to the ELP: An e-portfolio for autonomous language learning. Language Learning in Higher Education. 2016, 6, 2. P. 435-441.

[3] Cavana, P. Autonomy and self-assessment of individual learning styles using the European Language Portfolio (ELP). Language Learning in Higher Education. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/cercles-2011-0014.

[4] Carras, C. et al. Le Français sur Objectifs Spécifiques et la classe de langue. CLE international, 2007.

[5] Cuq, J. P. Cours de la didactique du français langue étrangère et seconde. Grenoble, Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 2017.

[6] Dexter, P. - Sheerin, S. Learner Independence Worksheets. IATEFL, 1999.

[7] Ellis, G. - Sinclair, B. Learning to Learn English, A Course in LAnguage Training. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

[8] European Language Portfolio for learners up to the age of 11. 2002.

[9] European Language Portfolio for learners aged 11 to 15. 2001.

[10] European Language Portfolio for learners aged 15 – 19. 2009.

[11] Han, A. Gaining insights into student reflection from online learner diaries. Language Learning in Higher Education. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/cercles-2011-0013.

[12] Holec, H. Apprendre à apprendre et apprentissage hetéro-dirigé. Le français dans le monde. 1992.

[13] Hutchinson, T. - Waters, A. English for Specific Purposes: a Learning-Centred Approach. Cambridge University Press, 1987.

[14] Chamot, A.U. Language learning strategy instruction: Current issues and research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 2005, 25. P. 112-130.

[15] Choděra, R. Výuka cizích jazyků na prahu nového století, II.. Ostrava: Ostravská univerzita, 2002.

[16] Janíková, V. et al. Výuka cizích jazyků. Praha: Grada, 2011.

[17] Comenius, J.A. Nejnovější metoda jazyků, Vybrané spisy J.A. Komenského. Praha: SPN, , 1658, vydání 1964.

[18] Oxford, R. Language Learning Strategies, What Every Teacher Should Know. Boston, Heinle & Heinle, 1990. p. ISBN .

[19] Petty, G. Teaching Today. Nelson Thornas Ltd, 1998.

[20] Průcha, J. et al. Pedagogický slovník. Praha: Portál, 2009.

[21] Robson, S. Self-regulation and metacognition in young children: Does it matter if adults are present or not. British Educational Research Journal. 2016, 42, 2. P. 185-206.

[22] Rogers, A. Teaching Adults. Open University Press, 2010.

[23] Thoutenhoofd, E.D. - Pirrie, A. From self-regulation to learning to learn: observations on the construction of self and learning. British Educational Research Journal. 2013, 41, 1. P. 72-84.

[24] Vlčkova, K. Strategie učení cizímu jazyku, Výsledky výzkumu používání strategií a jejich efektivity na gymnáziích. Brno: Paido, 2007.

[25] Vlčková, K. - Bradová, J. Slabý vztah strategií učení a výsledků vzdělávání: Problém operacionalizace a měření?. Studiapaedagogica. [online] 2014. Availiable at: <DOI: 10.5817/SP2014-3-2>.

[26] Zhoc et al. Emotional Intelligence (EI) and self-directed learning: Examining their relation and contribution to better student learning outcomes in higher education British. Educational Research Journal. 2018, 44, 6. P. 982-1004.

[27] Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner. [online], [Cited 26 April 2019] , 2002. Availiable at: <http://mathedseminar.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/94760840/Zimmerman%20-%202002%20-%20Becoming%20a%20Self-Regulated%20Learner%20An%20Overview.pdf>.

Analysed textbooks: Series „In Use“:[28] Farrall, C. Professional English in Use, Marketing. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

[29] MacKenzie, I. Professional English in Use, Finance. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

[30] Mckeown, A. - Wright, R. Professional English in Use, Management. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

[31] Brown, G.D. Professional English in Use, Law. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[32] Mascull, B. Business Vocabulary in Use, Elementary to Pre-Intermediate. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[33] Mascull, B. Business Vocabulary in Use, Intermediate. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

[34] Mascull, B. Business Vocabulary in Use, Advanced. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Series DELTA Business Communication Skills:[35] Lowe, S. Telephoning, DELTA Business Communication Skills. Delta Publishing, 2004.

[36] Pile, L. E-mailing, DELTA Business Communication Skills. Delta Publishing, 2004.

[37] King, D. Socialising, DELTA Business Communication Skills. Delta Publishing, 2005.

[38] Lowe, S. - Pile, L. Presenting, DELTA Business Communication Skills. Delta Publishing, 2006.

[39] Lowe, S. - Pile, L. Negotiating, DELTA Business Communication Skills. Delta Publishing, 2007.

[40] King, D. Meetings, DELTA Business Communication Skills. Delta Publishing, 2008.

Series „Effective…“:[41] Comfort, J. Effective Negotiating, Oxford Business English Skills. Oxford University Press, 1998.

[42] Comfort, J. Effective Meetings, Oxford Business English Skills. Oxford University Press, 1996.

[43] Comfort, J. Effective Socializing, Oxford Business English Skills. Oxford University Press, 1997.

[44] Comfort, J. Effective Presentations, Oxford Business English Skills. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Series Market Leader:[45] Widdowson, A. R. Business Law, Market Leader. Pearson Longman, 2010.

[46] Pilbeam, A. O’Driscoll, N. Logistics Management, Market Leader. Pearson Longman, 2010.

[47] O’Driscoll, N. Marketing, Market Leader. Pearson Longman, 2010.

Series of the Czech “Fraus” publisher:[48] Gutjahr, L. - Mahoney, S. English for Sales and Purchasing. Prague: Fraus, 2009.

Series Macmillan:[49] Emmerson, P. Email English. Macmillan, 2001.

[50] Barrett, B. - Sharma, P. Networking in English. Macmillan, 2010.

[51] Hughes, J. Telephone English. Macmillan, 2006.

[52] WIlliams, E.J. Presentations in English. Macmillan, 2008.

Other mentioned textbooks:[53] Harding, K. - Taylor, L. International Express Intermediate. Oxford University Press, 2011. p. ISBN .

[54] Brookhart, G. Business Benchmark Advanced. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Zpět na obsah / Back to content