| Ročník: 2015 | Volume: 2015 |

| Číslo: 1 | Issue: 1 |

| Vyšlo: 1.července 2015 | Published: July 1st, 2015 |

| Igoni, Joy Sade - Peters, Brenda.

The necessity of Policy/Legislation for implementation of Early Intervention for Children with Disability: A case/context in Nigeria.

Paidagogos, [Actualized |

#14

Zpět na obsah / Back to content

The necessity of Policy/Legislation for implementation of Early Intervention for Children with Disability: A case/context in Nigeria

Abstract: The enactment of early intervention legislation ensures that all children with disabilities from birth to the age of three receive appropriate early intervention services. This policy or legislation is the rules and regulations for a country guiding the practice of early intervention, as well as stipulating the rights of children with disabilities. It acts as a guideline to Local, State, Federal government and other allied agencies in providing and establishing the necessary system of early intervention services. With regards to special education and early intervention for children or adults with disabilities in Nigeria, the only mandate comes from Section 8 of the National Policy on Education. However, there is no legal mandate from the government to carry out the objectives enumerated in Section 8 of the National Policy on Education with regards to children or adults with disabilities. For early intervention to be implemented effectively in Nigeria there must be an enacted Federal law, which will aid children with disabilities and their families. The aim of this paper is to describe the status of policies or legislation/law, with regards to implementation of early intervention for children with disabilities in Nigeria. Methodology: the study employed the use of simple descriptive statistics, and used questionnaires, unstructured interviews and literature reviews. The participants (57 females and 36 males) included mostly professionals involved in early intervention for children with disabilities, and parents of children with disabilities in Nigeria. The study found that Government budgetary plan to implement a legal support or pass a bill in line with the enumerated objectives in Section 8 of the National Policy on education is minimal or non-existent. In addition, Government’s support in terms of needed resources/facilities is substituted for edible items for moral boosting. Lastly, government has a nonchalant attitude towards early intervention policy and support to parents and children with disabilities. Thus, it was deduced that Nigeria lacks a policy or law/legislation on early intervention practice.

Keywords: Government policy/legislation, early intervention, children with disabilities in Nigeria.

Introduction

Legislatively, early intervention is used to describe the years from birth to age 3, although the terms early childhood special education or pre-school special education have been used to describe the period of pre-school years (ages 3-5) according to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA). Part C, which addresses services for children from birth to age 3 and their families and section 619 of Part B, which covers services for children ages 3 through 5 (Bruder, 2010). The Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 initially mandated services for children with disabilities (Lanzi, Ramey and Ramey 2007). Bruder (2010) further explained that in 1986, Public Law 99-457 was passed as amendments to IDEA (20 U.S.C. Secs. 1471 et seq.). This law mandated pre-school services for children with disabilities and extended to them all rights and protection under IDEA Part B, (Section 619).In United States and other countries, early intervention services and practices are mandated through federal legislation. The Education for All Handicapped Act Amendments of 1986 provided additional funds for children from ages 3-5 and also funded the creation of a system of early intervention for children from birth to their third year of age. Currently, early intervention services are funded by Part C (birth to 3 years) of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Amendments of 1997 (Lanzi, Ramey and Ramey 2007;Keilty, 2010). In most European countries, there are established social policies that exemplify early intervention, in addition to progressive family policies that cater for parental leave, childcare, home-health visiting and family support programmes. For instance, the European social policy infrastructure includes income transfers, health care, and housing assistance, which provide a solid basis for supporting child and family services (Kamerman, 2000 in Lanzi, Ramey & Ramey 2007). Most importantly, Turnbull et al., (2007) in Bruder (2010), noted that both Part C and Part B under the law recognize the importance of families in the provision of services.

Aim of the research – To describe government policy/legislation and supports towards early intervention for children with disabilities in Nigeria. And the urgent need to develop and enact Federal laws/legislations aimed at young children with disabilities and their families, and providing necessary support needed for effective implementation of early intervention.

Government Policy, Legislation and supports for Early Intervention of children with disability in Nigeria

Nigeria is a signatory to United Nations Edict on Human Rights and Child Right, which stipulates that a child has a right to be free, enjoy leisure and play, and be protected from harmful practices, violence, injury, and abuse. On the above basis, Nigeria promulgated a decree in 1993 for the provision of clear and comprehensive legal protection and security for Nigerians with disabilities (Eskay, Onu and Igbo 2012). Children and youth with disabilities are yet to be provided with necessary intervention services and programmes, as well as free education as stipulated by the decree. The Policy helped in the formulation and implementation of special education programmes for children with disabilities in various countries (Eskay, Onu and Igbo 2012).In any democratic society, no programme can be successful without a legal enforcement. In regards to special education or early intervention for children or adults with disabilities in Nigeria, the only mandate comes from Section 8 of the National Policy on Education. However, there is no legal mandate from the government to implement the objectives enumerated in Section 8 of the National Policy on Education with regards to people with disabilities. The absence of legal mandate has led to civil rights violation, and the lack of adequate programming (Eskay, Onu, Igbo, Obiyo and Ugwuanyi, 2012).

Ajuwon (2008) in Eskay et al., (2012) also pointed out that the absence of legal mandates to enforce special education programmes, as well as early intervention, perpetuates negative societal perceptions of children and adult with disabilities. Furthermore, Ajuwon (2008) contends to the lack of human knowledge about the legal mechanism that affects “(1) the knowledge of who should be served, why he/she should be served, how he/she should be served and where he/she should be served; (2) procedural safeguards and due process rights; (3) non-discriminatory identification and assessment; (4) confidentiality of information; (5) individualized educational programming and intervention; (6) parental rights and responsibilities; and (7) appropriate categorization, placement and instruction” (p.480). Nevertheless, the practices of polices in the National Policy on Education are yet to be implemented, thus, rendering the objectives enumerated less functional (Eskay, Onu, and Igbo 2012). Though, Nigeria made a decree in 1993 for the provision of clear and comprehensive legal protection and security for Nigerians with disabilities, the decree was resubmitted as a bill to be signed by the Senate in 2011 (Eskay, Onu and Igbo 2012).

Moreover, the policy’s document neither classified criteria for personnel training nor co-ordination of its special education unit (Eskay, Onu and Igbo 2012). However, effective implementation and legal backup for children clinics for early identification, curative measures and medical care for children with disabilities as stated in the policy failed. Consequently, the preceding situation led to the stagnation of special education and early intervention in Nigeria. Most importantly, the lack of legal enforcement on ‘National Policy on Education’ and ‘Nigeria and The Rights of the child’ has impeded:

- Special education progress;

- Early intervention services and programmes for children and adult with disabilities;

- Parental rights to due process are denied;

- Parents and professionals involvement in intervention services and programmes. Thus, making children and adults with disabilities to suffer as well as being treated as third class citizens.

The lack of effective legislature has resulted into failure of government in supporting early intervention/early childhood special education, as well as support to parents and families of children with disabilities. Although, there is evidence of budgetary allocation of 2% to UBEC, however, the fund hardly gets to appropriate agencies that should use it effectively for special needs provision (Ubani, 2012). Furthermore, Ubani (2012) opined that since nothing is happening in terms of providing or supporting early intervention services for children with disabilities in their early years, there is need to revisit existing policies on early childhood, so as to accommodate and support the interests and needs of children with disabilities.

Participants

The participants were 57 females and 36 males. They were mainly professionals, who are involved in the practice of early intervention for children with disabilities, as well as parents of children with disabilities in Nigeria.

Methods and Instrument

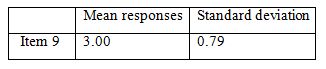

Three methods are combined for the study. These include: literature reviews, questionnaire and unstructured interview. The major instrument used was questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised of two parts. The first part contained the bio-data of participants. The second part focused on items that investigate and describe the available government policy or legislation and supports toward early intervention for children with disabilities. Copies of the instrument were distributed and collected as correctly filled by the participants. The questionnaire was scored 4, 3, 2, 1, and 0 for strongly agree, agree, not sure, disagree and strongly disagree respectively. Data collated from the Likert scale (i.e. data gathered from the participants) were analyzed with the use of simple descriptive statistical of frequency counts, mean, and standard deviation. Thus, it was presented in graphs to describe the prevailing situation.

Interpretation of Findings

From figure 1, the findings show that majority of the respondents disagreed and strongly disagreed, which implies that the country lacks a legal support for early intervention.

It can be seen (figure 2) that greater number of the respondents disagreed. This implies that the available legislation/policy is not effective.

Most of the respondents disagreed (figure 3), which implied that they were not satisfied with the legal support for caring for children with disabilities.

Although, some respondents were not sure, however, majority of them strongly agreed, while others agreed (figure 4), which implied that government priority is minimal in the implementation of policy/legislation for early intervention.

Majority of the respondents disagreed, followed by those who strongly disagreed (figure 5), implying that existing government policy does not enhance the practice of early intervention for children with disabilities.

From figure 6, nearly all the respondents disagreed which implies that health care support for early intervention of children with disabilities is not provided by the government.

Majority of the respondents disagreed (figure 7), implying that they do not receive any financial support from the government.

Notably, respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, although, majority disagreed (figure 8). Thus, it implied that from birth (0 year) to 3years, no necessary care/support had been given to parents and families of children with disabilities.

Majority of the respondents agreed, followed by those who strongly agreed (figure 9), which implied that most resources were substituted, but instead presented as gift to parents and families of children with disabilities as government support.

Most of the respondents strongly agreed, although, majority agreed (figure 10), which implied that nonchalant attitude of government toward supporting of early intervention seems to be increasing.

Discussion of Findings

In sum, accordingly, the descriptive findings from figures 1–10 above show results for items 1–10 derived from the questionnaires administered to both professionals and parents. This was intended for acquiring information on government policy or legislation, support for early intervention and its practice for children with disabilities including their respective parents and families in Nigeria. It can be seen that majority of the respondents disagreed and strongly disagreed. This implies that the country lacks a policy/legislation on early intervention practice. Thus, minimum or non-existent support is given to parents and families of children with disabilities. However, minority of the respondents agreed and strongly agreed that government policy (National policy on Education) is in place, although not implemented. Nevertheless, few respondents were not sure because they have not heard or seen any policy/legislation. Similarly, they did not receive any support from the government.

Figure 4, specifically seeks to find out the priority of government towards the implementation of policy/legislation for early intervention and special education as stated in the National Policy on Education Section 8. It can be deduced that majority of the respondents strongly agreed and agreed that the priority of the government to implement such legal support is minimal. On the other hand, the minority of the respondents were not sure. The above could imply that the people do not know if the government priority to implement a legal support or pass a bill in line with the policy is minimal or non-existent. Nonetheless, few respondents disagreed and strongly disagreed, which suggests that the government priority to implement the legal support is not minimal.

Figure 9 attempts to find out government support for early intervention. It can be seen that most respondents agreed as well as strongly agreed. This means that facilities/resources needed for early intervention are substituted for edible item, a form of moral boosting by the government. Nevertheless, very few respondents disagreed and others not sure. Revealing that most edible items received as support from government may not be equated to replacing the resources/facilities needed, but a concern on the part of the government.

Lastly, figure 10 seeks to find out the attitude of government to early intervention, policy and support from parents and professionals. Greater number of the respondents strongly agreed and agreed. This could denote that government has a nonchalant attitude towards early intervention policy and support to parents and children with disabilities. However, few respondents strongly disagreed and disagreed that the nonchalant attitude of the government is due to unforeseen circumstances. Notwithstanding, minority of the respondents were not sure, which could also signify that not nonchalant attitude or unforeseen circumstance on the part of the government is responsible.

Conclusion

It is obvious from the findings that there is no law or policy/legislation legalizing the practice of early intervention for children with disabilities in Nigeria. As a result, it is difficult to mandate intervention for children with disabilities as early as possible. For instance, government support is lacking, as well as minimal priority in passing a bill to the existing policy. Eskay, Onu and Igbo (2012) refers to the preceding situation as associated problems of early intervention programme facing Nigeria, including lack of enforced legislation and non-existence of facilities. Although, Ubani (2012) stated that, nothing is happening in terms of providing a new law or policy/legislation, and supporting early intervention services for children with disability in their early years. However, there is need to revisit the existing policies in early childhood. This will help to accommodate, support the interests and needs of children with disabilities and their respective families. Consequently, enacting a revised Policy in Nigeria is a necessity to effectively implement early intervention practices and services for children with disabilities, as well as their respective families.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, a comprehensive policy, legislation or law on public provision of early intervention programmes and services for children with disabilities aged birth to seven should be developed as a matter of urgency. This is needed in Nigeria because there are no clear policies and laws on early intervention and education of children or persons with disabilities. Nigeria should have a special education Act of Parliament. This Act will give children with disabilities a legal right to intervention and education, with the government having certain obligations to fulfill. More so, the policy should state the financial aspect of the intervention as regards to each child and their families. All areas that require financial support by the government should be covered by clear policies/laws including health care, support equipment and devices, food and shelter, security and education.

Government should have a positive attitude in the implementation of such policies/laws on early intervention of children with disabilities. Thus, a penalty or fine should be included in the policies/laws on any negative or nonchalant attitude towards infants, toddlers and children with disabilities.

Lastly, Federal and State government should provide appropriate supports to parents and families of children with disabilities and not leaving them to carry their responsibilities alone.

Dedication: This research was supported by the grant UPOL PdF 2014007 and CZ.1.07/2.3.00/30.0004

Reference

[1] Bruder, M.B. Early Childhood Intervention: A Promise to Children and Families for their Future. Council for Exceptional Children. 2010, 76, 3. ISSN 0014-4029.

[2] Eskay, M. et al. A Review of Special Education Services Delivery in the United States and Nigeria: Implications for Inclusive Education. US-China Education Review. 2012, B 9. P. 824-831. ISSN 1584-6613.

[3] Eskay, M. et al. Disability within the African Culture. US-China Education Review. 2012, B 4. P. 473-484. ISSN 1548-6613.

[4] Keilty, B. The Early Intervention Guidebook for Families and Professionals: Partnering for Success. New York: Teachers College Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8077-5026-1.

[5] Lanzi, R.G. - Ramey, C.T. - Ramey, S.L. Early Intervention Research, Services and Policies. In Slater, A. - Lewis, M. (ed.) Introduction to Infant Development. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. P. 291-302.

[6] Ubani, S.N. Early Childhood Education Services Delivery for Children with Special Educational Needs in Nigeria. The Special Educator. 2012, 11, 1. ISSN 1597-1767.

Zpět na obsah / Back to content